| BIO 554/754

Ornithology Bird Biogeography |

|

| BIO 554/754

Ornithology Bird Biogeography |

|

Loon-like toothed bird Hesperornis regalis

swims

through the Cretaceous sea

(Painting by Dan Varner; source: www.dmr.nd.gov/ndfossil/Education/trunks/Trunk%20030609.html)

What does the fossil record reveal concerning the present-day distribution of birds? The study of historical bird geography is difficult because of the many variables involved: evolution, climatic change, shifting vegetation, weather disasters, epizootics, rapid dispersal, ecological adaptation, competition between species, and barriers (Welty & Baptista 1988). However, it is known that (Proctor and Lynch 1993):

| Fossil

Evidence for the Extant Avian Radiation in the Cretaceous -- Clarke

et al. (2005) provide apparent evidence that cousins of living birds

coexisted

with dinosaurs more than 65 million years ago. Information from a new

species

called Vegavis

iaai indicates that these birds lived in the Cretaceous and

must

have survived the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) mass extinction event that

included the disappearance of all other dinosaurs. Analysis of the

fossil,

discovered in Antarctica in 1992, revealed a new species in the

group

Anseriformes, which includes ducks and geese. The question of whether

relatives

of living birds co-existed with non-bird dinosaurs has evoked

controversy.

Some investigators, using “molecular clock” models and DNA

sequence

data as well as the distribution of living birds, have concluded that

relatives

of living birds must have existed alongside non-avian dinosaurs and

survived

the mass extinction of dinosaurs at the K/T boundary. Others believe

such

data are unreliable, that the fossil record shows no evidence of living

bird lineages in the Cretaceous, and that relatives of today’s birds

evolved

after the K/T boundary.

“We have more data than ever to propose at least the beginnings of the radiation of all living birds in the Cretaceous,” Clarke says. “We now know that duck and chicken relatives coexisted with non-avian dinosaurs. This does not mean that today’s chicken and duck species lived with non-avian dinosaurs, but that the evolutionary lineages leading to today’s duck and chicken species did.” |

Skrepnick shows Vegavis in the foreground with a duckbill dinosaur in the background (Source: www.ncsu.edu). |

The distribution of some groups of birds has likely been influenced by continental drift (Cracraft 1974). Some examples of taxa where evidence indicates that intercontinental connections influenced present-day distribution include:

Geographic Ranges of Birds

The distribution of a species is a consequence of its:

Given these various factors, where are the world's birds located?

There are now ~9700 species occupying the six zoogeographical

realms: Nearctic, Neotropical, Palearctic, Ethiopian (or African),

Oriental,

and Australasian.

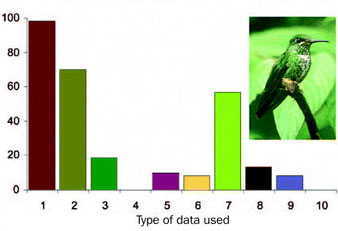

| Evaluating species limits in birds -- Watson (2005) examined sources of data used to diagnose new species and found variation among classes. New species of amphibians were typically diagnosed using external appearance, morphometrics, and external morphology, while reptiles were typically diagnosed using appearance and external morphology. Mammals were generally described using morphometrics, external morphology, and internal morphology, whereas new bird species diagnoses relied on external appearance, morphometrics, and behavior (see figure to the right). Birds were the only group described primarily using external appearance (98%; only one species description did not use plumage characteristics), compared with an overall frequency of 54% for the other three groups combined. Ecological data (distributional range, habitat, and behavior) were used for 62% of new bird descriptions, significantly more than the 14% for the other three classes combined. The use of molecular data was consistent across all four classes; by contrast, behavioral traits (typically vocalizations) were used for amphibians and birds but not for reptiles or mammals. |

Sources of data used to diagnose new species of birds (1993 - 2002). Data types: 1, appearance; 2, morphometrics; 3, external morphology; 4, internal morphology; 5, range; 6, habitat; 7, behavior; 8, molecular data; 9, karyology; 10, reproduction. Photograph of the Green-crowned Brilliant (Heliodaxa jacula) by David M. Watson. Of the 60 new bird species described, there were 7 owls, 7 tyrant flycatchers, 2 hummingbirds, and 1 parrot (see www.csu.edu.au/faculty/sciagr/eis/staff/watson.htm for details). |

Of course, some birds also occur beyond the borders of these realms on Oceanic islands and on Antarctica. Each realm & many islands have their characteristic birds; avifaunas that represent a mixture of species of various ages & origins.

Here's a brief summary of the avifaunas of these realms:

| Explosive speciation in Dendroica warblers -- The 27 species of Dendroica wood-warblers represent North America's most spectacular avian adaptive radiation. Dendroica species exhibit high levels of local sympatry and differ in plumage and song, but the group contrasts with other well-known avian adaptive radiations such as the Hawaiian honeycreepers and Galapagos finches in that Dendroica species have differentiated modestly in morphometric traits related to foraging. Instead, sympatric Dendroica tend to partition resources behaviorally and have become a widely cited example of competitive exclusion. Lovette and Bermingham (1999) explored the temporal structure of Dendroica diversification via a phylogeny based on 3639 nucleotides of protein-coding mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Comparisons with a null model of random bifurcation-extinction demonstrated that cladogenesis in Dendroica has been clustered non-randomly with respect to time, with a significant burst of speciation occurring early in the history of the genus, possibly as long ago as the Late Miocene or Early Pliocene. In North America, an abrupt rise in temperature & aridity occurred near the Miocene - Pliocene boundary, resulting in a reduction and fragmentation of forest habitats. By the Middle Pliocene, however, the continent-wide distribution of forest habitats was similar to present-day conditions. This sequence of paleoenvironmental changes suggests that the many Dendroica lineages may have initially differentiated allopatrically in the forest refugia of the Early Pliocene, followed by ecological reinforcement of adaptive differentiation during secondary contact in the expanded forests of the Middle Pliocene. |

|

|

Suboscines and Oscines Of the more than 3,700 species of Neotropical

birds, approximately

1,000 species are classified taxonomically as "suboscines." There are

only

about 50 suboscine species in all of the rest of the world, thus the

Neotropics

are unusual in harboring so many members of this group. The suboscines

are part of the huge order of Passeriformes, or perching birds. Most

passerines

in the world are true oscines, which means that they have a complex

musculature

of the syrinx, the part of the trachea that produces elaborate sounds,

such as the flutelike songs of various thrushes and solitaires or the

warbling

of a canary. Suboscines, however, have a considerably less complex

syringeal

musculature and typically have far more limited singing abilities than

true oscines. Neotropical suboscines have undergone two major adaptive

radiations, with the tyrant flycatchers, cotingas, and manakins

representing

one, and the woodcreepers, ovenbirds, true antbirds, ground antbirds,

gnateaters,

and tapaculos representing the other. No one knows why suboscines have

fared so well in the Neotropics, but the reason may simply be

historical.

For more information about birds of the neotropics, check out John

Kricher: A Neotropical Companion: Chapter 12. Neotropical Birds.

|

Summary of passerine bird distribution and basal relationships (Moyle et al. 2006)

Chesser (2004) study the phylogenetic relationships among New World suboscine birds using nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences. New World suboscines were shown to constitute two distinct lineages, one apparently consisting of the single species Sapayoa aenigma (Broad-billed Sapayoa), the other made up of the remaining 1000+ species of New World suboscines. With the exception of Sapayoa, monophyly of New World suboscines was strongly corroborated.

Moyle et al. (2006) used molecular and morphological data to derive a phylogenetic hypothesis for the Eurylaimides, an Old World bird group now known to be distributed pantropically, and to investigate the evolution and biogeography of the group. Phylogenetic results indicated that the Eurylaimides consist of two monophyletic groups, the pittas (Pittidae) and the broadbills (Eurylaimidae sensu lato), and that the broadbills consist of two highly divergent clades, one containing the sister genera Smithornis and Calyptomena, the other containing Pseudocalyptomena graueri, Sapayoa aenigma, the asity genera Philepitta and Neodrepanis, and five Asian genera. Their results indicate that over a ~10 million year time span in the early Tertiary, the Eurylaimides came to inhabit widely disjunct tropical regions and evolved disparate morphology, diet, and breeding behavior. Biogeographically, although a southern origin for the lineage is likely, time estimates for major lineage splitting do not correspond to Gondwanan vicariance events, and the biogeographic history of the crown clade is better explained by Laurasian climatic and geological processes. In particular, the timing and phylogenetic pattern suggest a likely Laurasian origin for the sole New World representative of the group, Sapayoa aenigma.

Flock of Red-billed Quelea (one of Africa's most abundant birds)

Secretary Bird

Photo by Doug Jansen

http://www.pbase.com/image/15614244

Common Hoopoe

| Southeast Asia has numerous geographic islands. The Malay Archipelago, as southeast Asia is known to biogeographers, covers 2,894,0000 square kilometers -- only twice the size of Alaska. Yet the region comprises at least 20,000 islands, of which 13,000 make up Indonesia in a chain 5,000 kilometers long between Asia and Australia. The Indonesian archipelago has not always been so broken up. When the sea level has dropped, as it has several times during the relatively recent past, many of the islands have merged to form a single territory, allowing their wildlife communities to mingle. When the seas have receded again, splitting up the prehistoric forests into fragments once more, each separate sector would follow its evolutionary path in response to its own set of local environmental conditions and selection pressures. Greater diversity and complexity result. When the seas advance again, there will have been a repeated mingling of biotas and more creative tension between disparate communities of animals and plants, which often leads to some extinctions but eventually fosters more speciation. The overall result is an exceptional amount of biotic diversity. Among the endemic species of birds, 94% are confined to a single island or a small group of islands. |

|

Pacific birds rewrite evolutionary textbook-- Evolutionary biologists have long assumed that species in island-rich areas

such as the Pacific Rim

diverge and evolve in a series of 'stepping-stone'

dispersals from one island to the next. But a new analysis of the family

tree of tropical Pacific

birds suggests that this cherished assumption is

not true.

Filardi and Moyle (2005) analysed DNA from a host of bird

species from the family

Monarchidae, commonly called Monarch

flycatchers. They found that the species seem to have colonized the

area not in a series of separate

stepping-stone excursions from continental

land masses, but in a single, even spread across all Pacific archipelagos.

The researchers support their

conclusion by pointing out that, of the six

different species groups that are confined to a single island chain, all are

embedded within a group, or

genus, called Monarcha. This genus is spread

across the entire tropical Pacific, showing that all of these remote species

arose from a single lineage.

What's more, the authors point out, some

species show evidence of having recolonized continental areas such as

Australia - contrary to the previous

idea that that species colonize island

chains only by moving away from continents.

Bird drawings are roughly to scale and illustrate some of the marked morphological differentiation between island endemics that

has complicated the evolutionary interpretation of the group. Colored circles indicate three classes of node age. Branch lengths are

not to scale. Large hatching outlines the distribution of Clytorhynchus and small hatching outlines the range of Monarcha cinerascens.

|

||

| Ancient

DNA Tells Story of Giant Eagle Evolution --

For reasons not entirely clear, when animals make their way to isolated

islands, they tend to evolve relatively quickly toward an outsized or

pint-sized

version of their mainland counterpart. One avian giant was found in New

Zealand: Haast's eagle (Harpagornis moorei), with a

wingspan

up to 3 meters. Though Haast's Eagle could fly, its body mass

(10–14

kilograms) pushed the limits for self-propelled flight. As extreme

evolutionary

examples, large island birds can offer insights into the forces and

events

shaping evolutionary change. Bunce et al. (2005) compared ancient

mitochondrial

DNA extracted from Haast's Eagle bones and found that the extinct

raptor

underwent a rapid evolutionary transformation that belies its kinship

to

some of the world's smallest eagle species. Their analysis places

Haast's

Eagle in the same evolutionary lineage as a group of small eagles in

the

genus Hieraaetus. Surprisingly, the genetic distance separating

the giant eagle and its smaller cousins from their last common ancestor

is relatively small.

Using molecular dating techniques, Bunce et al. (2005) proposed a divergence date of 0.7–1.8 million years ago. The increase in body size—by at least an order of magnitude in less than 2 million years—is remarkable, Bunce et al. (2005) argue, because it occurred in a species still capable of flight. The absence of mammalian competitors may have precipitated the rapid morphological shift. Haast's eagle, the authors wrote, “represents an extreme example of how freedom from competition on island ecosystems can rapidly influence morphological adaptation and speciation.” -- Source: (2005) Ancient DNA Tells Story of Giant Eagle Evolution. PLoS Biol 3(1): e20. |

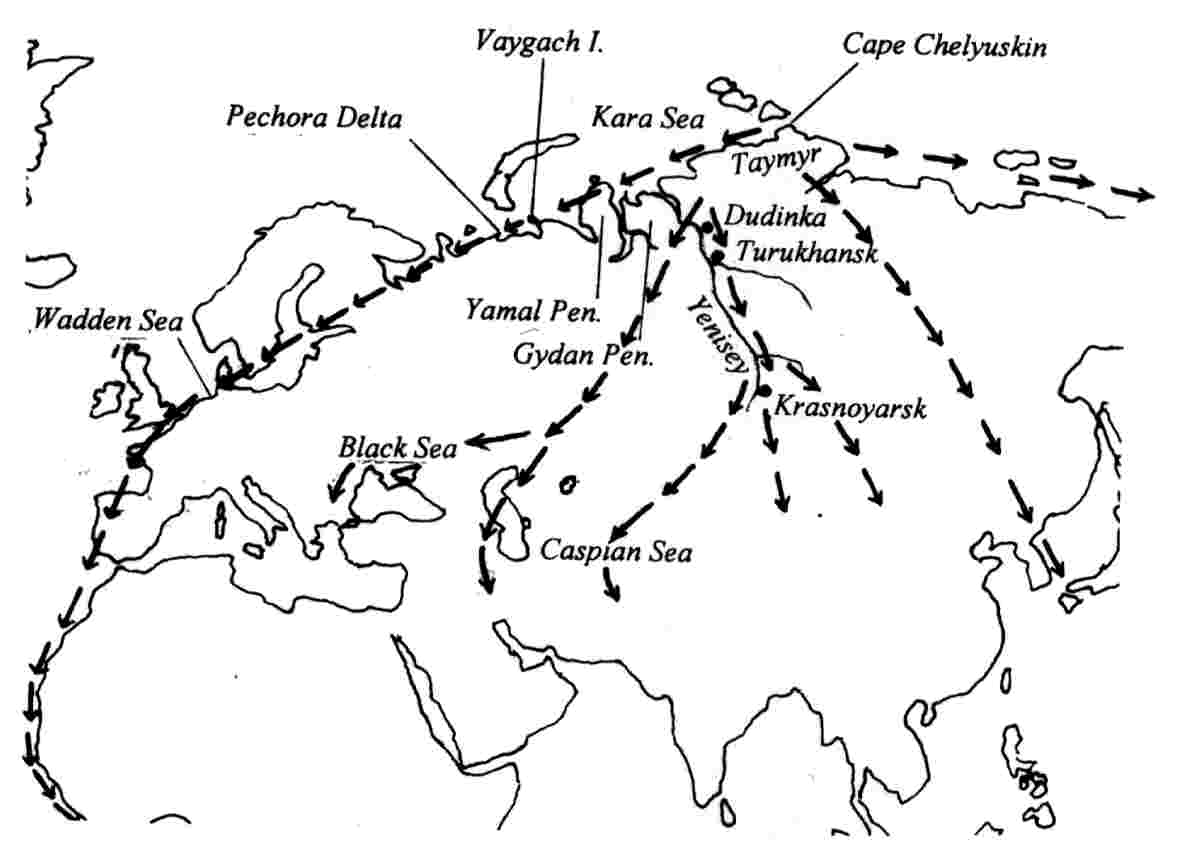

Avifaunas of the various zoogeographic realms represent a

mixture

of species of various ages & origins. The mobility of many (but not

all) birds, plus their proclivity to migrate, has allowed the movement

of some groups between realms - some very long ago, others more

recently.

And, once a species arrives in a new area, adaptive radiation often

generates

new species. This combination of avian mobility (or lack thereof) and

adaptive

radiation has created avifaunas that represent complex mosaics

(Gill  1995).

Briefly, the avifaunas of the major zoogeographic realms can be

described

as follows:

1995).

Briefly, the avifaunas of the major zoogeographic realms can be

described

as follows:

The Western Palearctic Avifauna (Blondel and Mourer-Chauviré 1998) -- Compared with that of the two other large forested regions of the Northern Hemisphere (eastern North America and eastern Asia), the bird fauna (and particularly forest avifauna) of the western Palearctic is relatively species poor. Controlling as much as possible for the size of areas, Mönkkönen and Viro (1997) have shown that the western Palaearctic (including North Africa) has 50% fewer forest-associated bird species than eastern Asia and 40% fewer than eastern North America. Europe is similar in size to China (9 500 000 km2, including Manchuria), but European species  richness (about 500 bird spp.) is only about half that reported for China. In the western Palaearctic, less than half of the terrestrial avifauna is associated with forest compared with two-thirds in eastern North America and eastern Asia.

richness (about 500 bird spp.) is only about half that reported for China. In the western Palaearctic, less than half of the terrestrial avifauna is associated with forest compared with two-thirds in eastern North America and eastern Asia.

Large and repeated habitat changes during the Pleistocene have undoubtedly accelerated the extinction rates of birds of the western Palearctic, just as they did for plants and large mammals in North America. Comparative analyses using molecular phylogenies of 11 lineages of North American songbirds also indicate a general decrease in rates of species diversification during the Pleistocene. However, molecular evolutionary trees cannot distinguish between reduced speciation rates (e.g. as a consequence of progressive niche filling through evolutionary time) and higher extinction rates as the cause of net changes in diversification rates.

Assuming similar rates of speciation over the whole Northern Hemisphere during the Pleistocene, the relative impoverishment of the western Palearctic bird fauna (compared with the two other regions of the Northern Hemisphere) could be caused by higher extinction rates in the western Palearctic, because there was no connection with the tropical biomes further south. In contrast to those of the western Palearctic, the extant bird faunas of both northeastern North America and eastern Asia share many species in common with southern tropical regions. For example, 76% of passerine species breeding in North America have either conspecific populations or congeneric species that breed in the Neotropics. In eastern Asia, two orders and nine families are tropical, whereas Afro-tropical influence in the fauna of the western Palaearctic is negligible.

The most likely explanation for these differences is that the biota of both eastern North America and eastern Asia remained connected to the tropics over the whole Tertiary–Quaternary, making it possible for a continuous interchange between tropical and temperate avifaunas. In contrast, the massive east–west oriented barriers (mountain ranges, seas and large desert belts) ‘trapped' biota of the western Palaearctic in their southern refugia during glacial periods, preventing them from finding refuge in tropical regions further south, and preventing tropical species from colonizing northern regions. Since the Pliocene, the Sahara desert has never been sufficiently forested to provide a dispersal corridor for forest birds between the Afro-tropics and Eurasia.

| Deciduous forest may have barely existed in the southern USA at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Contrary to most of the earlier interpretations, it now seems inappropriate to show any significant area of deciduous forest in the eastern US for the LGM. Current work by S. Jackson (Northern Arizona University), Eric Grimm (Illinois State Museum), and Bill Watts suggests that even in the south there was very little broad-leaved forest at the LGM, with perhaps only isolated pockets of deciduous forest that were surrounded by coniferous vegetation. These deciduous forest pockets at the LGM may have been confined to moister microsites, such as stream gullies (Ritchie 1982). For example, spruce forest has been found to have been growing in Louisiana at the LGM. Tallis (1990) also maps a south-eastern pine forest that extending from about 33°N down to the Gulf coast and northern Florida, and suggests that it would generally have been fairly open in structure. Source: http://www.soton.ac.uk/~tjms/namerica.html |

Source: http://www.esd.ornl.gov/projects/qen/NAL2215.gif & http://www.esd.ornl.gov/projects/qen/nercNORTHAMERICA.html |

A, Summer pattern of species richness across North America on the basis of expected number of species over three randomly chosen Breeding Bird Survey routes per 20,000-km2 grid cell. B, Spatial pattern of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in June at 1-km resolution. C, Winter pattern of species richness across North America on the basis of expected number of species over one randomly chosen Christmas Bird Count circle per 20,000-km2 grid cell. D, Spatial pattern of NDVI in December at 1-km resolution (From: Hurlbert and Haskell 2003). |

| Turacos are uniquely African, with 23 species recognized by most authorities. The forest-living species are undoubtedly among the most spectacularly colorful of birds, while the savanna-dwellers (known as "go-away birds" because of a well-known call, a harsh "kay-waaay") are predominantly grey in plumage. In South Africa, these birds are better known as louries. All are frugivores, specializing in fruit (particularly figs) and sometimes feeding on leaves, buds and flowers. They are usually gregarious, and frequently associate with parrots, hornbills and barbets, with individuals and groups often returning day after day to the same fruiting tree, until the crop is exhausted. |

White-bellied Go Away Bird |

| Birds & the Beetles --

Batrachotoxins are

neurotoxic steroidal alkaloids first isolated from a Colombian

poison-dart

frog. In 1992, the toxic principle from feathers and skin of birds in

the

genus Pitohui, endemic to New Guinea, was isolated and, remarkably,

proved

to be mainly a batrachotoxin (BTX). BTXs were later found in New Guinea

toxic birds of the genus Ifrita. On a weight basis, the batrachotoxins

are among the most toxic natural substances known, being 250-fold more

toxic than strychnine. It is believed that such toxins provide some

protection

against the birds' natural enemies, such as parasites and predators,

including

humans. Neither poison-dart frogs or birds are thought to produce the

toxins

de novo, but instead they likely sequester them from dietary sources.

Dumbacher

et al. (2004) described the presence of high levels of batrachotoxins

in

a little-studied group of beetles, genus Choresine (family Melyridae).

These small beetles and their high toxin concentrations suggest that

they

might provide a toxin source for the New Guinea birds. Stomach content

analyses of Pitohui birds revealed Choresine beetles in the diet, as

well

as numerous other small beetles and arthropods. The family Melyridae is

cosmopolitan, and relatives in Colombian rain forests of South America

could be the source of the batrachotoxins found in the highly toxic

Phyllobates

frogs of that region.

The Blue-capped Ifrita (Ifrita kowaldi; shown to the right) is called Nanisani by local villagers. Nanisani is also the word used to describe the tingling and numbing sensation of the lips and face that results from contacting both beetles and bird feathers (Photo Source: Smithsonian National Zoological Park). |

A Choresine pulchra beetle with an insert showing glandular vesicles.

|

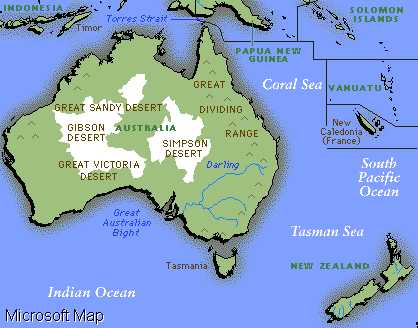

| Songbirds

Escaped From Australasia, Conquered Rest of World - That

male cardinal singing his heart out in your backyard has ancestors that

left the neighborhood of Australia 45 million years ago. A

comprehensive

study of DNA from songbirds and their relatives by Barker et al. (2004)

shows that these birds, which account for almost half of all bird

species,

did not originate in Eurasia, as previously thought. Instead, their

ancestors

escaped from a relatively small area—Australasia (Australia, New

Zealand

and nearby islands) and New Guinea—about 45 million years ago and went

on to populate every other continent save Antarctica.

The movement of

the Australia/New

Guinea plate between 60 (a) and 20 (b) million years

ago

(Mya). When New Zealand

The order Passeriformes, or perching birds, includes all songbirds, such as robins, cardinals, blackbirds, house sparrows, house finches and crows. The group is further divided into birds that must learn their songs “true songbirds” (oscines) and those with the innate ability to sing the “correct” song. True songbirds account for 4,580 of the 6,000 known Passeriformes species. The true songbirds are currently divided into two groups: Passerida (3,477 species, among them many familiar backyard species) and Corvida (1,103 species, including crows and ravens). The two groups of true songbirds were thought to have separate origins, with Corvida originating in Australasia and the Passerida in Eurasia. The Passerida then supposedly spread from Eurasia to Africa, Australasia and the New World. But in examining the DNA sequences of two genes in all but one family (a closely related group, such as “crows and jays” or “warblers”) of passerine birds, Barker et al. (2004) made a startling discovery. “It was thought that the Passerida arose in Eurasia about 40 million years ago,” said Barker. “But we found that these birds fall into a group within the Corvida. That means all songbirds trace their origins to Australasia and New Guinea.” The Passerida differ from the Corvida because the Passerida somehow made it out of Australasia and New Guinea and onto the Asian mainland long before the Corvida, Barker said. Asia and Australasia are carried on separate plates in the Earth’s crust, and for many millions of years those plates were far apart. Around 45 million years ago, the ancestors of the Passerida dispersed to Asia—over more than 600 miles of open ocean--long before these two plates approached one another (as shown on map with locations of the continents 45 mybp). For some reason, however, ancestors of the Corvida didn’t make it until about 25 million years later, or 20 million years before today. At that time, Asia and Australia were much closer to each other, and island chains that could have allowed the Corvida ancestors to “island hop” to the mainland appeared, Barker said. “There are many endemic Corvida birds on the

Indonesian

island of Lombok but very few on Bali, the next island to the west,”

said

Barker. “And, sure enough, the line separating the Asian plate from the

Australasian plate runs between Bali and Lombok.

|

Summary of passerine bird distribution and basal relationships (Moyle et al. 2006)

Photo © Arthur Grosset

Birds of Peru

Rainforest slide show

Literature cited

Avise, J.C. 2000. Phylogeography: the history and formation of species. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Avise, J.C. and D. Walker. 1998. Pleistocene phylogeographic effects on avian populations and the speciation process. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B 265:457-463.

Baker, A.J. 1991. A review of New Zealand ornithology. Current Ornithology 8:1-67.

Barker, F.K., A. Cibois, P. Schikler , J. Feinstein, and J. Cracraft. 2004. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:11040-11045.

Blondel. J. and Cécile Mourer-Chauviré. 1998. Evolution and history of the western Palaearctic avifauna. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 13: 488-492.

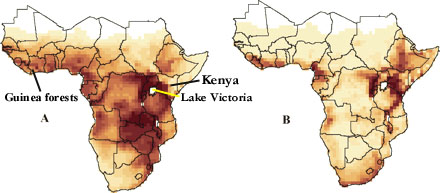

Brooks, T., A. Balmford, N. Burgess, J. Fjeldsa, L. A. Hansen, J. Moore, C. Rahbek, and P. Williams. 2001. Toward a Blueprint for Conservation in Africa. BioScience 51: 613-624.

Bunce, M., M. Szulkin, H. R. L. Lerner, I. Barnes, B. Shapiro, A. Cooper, and R. N. Holdaway. 2005. Ancient DNA Provides New Insights into the Evolutionary History of New Zealand's Extinct Giant Eagle. PLoS Biology 3(1): e9.

Chesser, R. T. 2004. Molecular systematics of New World suboscine birds. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32:11-24.

Clarke, J. A., C. P. Tambussi, J. I. Noriega, G. M. Erickson, and R. A. Ketcham. 2005. Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous. Nature 433: 305-308.

Cracraft, J. 1974. Continental drift and vertebrate distribution. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 5:215-261.

Darlington, P.J. 1957. Zoogeography: the geographical distribution of animals. J. Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

Dumbacher, J. P., A. Wako, S. R. Derrickson, A. Samuelson, T. F. Spande, and J. W. Daly. 2004. Melyrid beetles (Choresine): A putative source for the batrachotoxin alkaloids found in poison-dart frogs and toxic passerine birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 15857-15860.

Feduccia, A. 1995. Explosive evolution in Tertiary birds and mammals. Science 267:637-638.

Feduccia, A. 2003. 'Big bang' for Tertiary birds? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 18:172-176.

Filardi, C. E. and R. G. Moyle. 2005. Single origin of a pan-Pacific bird group and upstream colonization of Australia. Nature 438: 216-219.Gill, F.B. 1995. Ornithology, second ed. W.H.

Freeman

and Co., New York, NY.

Heinsohn, R. and M. C. Double. 2004. Cooperate

or speciate: new theory for the distribution of passerine birds.

Trends

in Ecology and Evolution 19: 55-57.

Hurlbert, A. H. and J. P. Haskell. 2003. The effect of energy and seasonality on avian species richness and community composition. American Naturalist 161:83-97.

Jetz, W. and C. Rahbek. 2001. Geometric constraints explain much of the species richness pattern in African birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 98:5661-5666.

Karr, J.R. 1990. Birds of tropical rainforest: comparative biogeography and ecology. Pp. 215-228 in Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities (A. Keast, ed.). SPB Academic Publ., The Hague, Netherlands.

Klicka, J. and R.M. Zink. 1997. The importance of recent Ice Ages in speciation: a failed paradigm. Science 277:1666-1669.

Lever, C. 1987. Naturalized birds of the world. Longman Scientific & Technical, Essex, England.

Levey, D.J. and F.G. Stiles. 1992. Evolutionary precursors of long distance migration: resource availability and movement patterns in Neotropical landbirds. American Naturalist 140:447-476.

Lovei, G.L. 1989. Passerine migration between the Palearctic and Africa. Current Ornithology 6:143-174.

Lovette, I. J. and E. Bermingham. 1999. Explosive speciation in the New World Dendroica warblers. Proc. Roy. Soc. London B 266: 1629-1636.

MacArthur, R.H., H. Recher, & M.L. Cody. 1966. On the relation between habitat selection and species diversity. Am. Nat. 100:319-332.

MacArthur, R.H. and E.O. Wilson. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ.

Mayr, E. 1946. History of the North American bird fauna. Wilson Bulletin 58:3-41.

Mayr, E. 1964. Inference concerning the Tertiary American bird faunas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 51:280-288.

Mengel, R.N. 1964. The probable history of species formation in some northern wood warblers (Parulidae). Living Bird 3:9-43.

Mönkkönen, M. and P. Viro. 1997. Taxonomic diversity of the terrestrial bird and mammal fauna in temperate and boreal biomes of the northern hemisphere. J. Biogeogr. 24: 603–612.

Moreau, R.E. 1952. Africa since the Mesozoic: with particular reference to certain biological problems. Proc. Zool. Soc. London 121:869-913.

Moyle, R.G., R. T. Chesser, R. O. Prum, P. Schikler, and J. Cracraft. 2006. Phylogeny and evolutionary history of Old World suboscine birds (Aves: Eurylaimides). American Museum Novitates 3544: 1–22.

Porter, W. F.. 1994. Family Meleagrididae (Turkeys) in del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World, Vol. 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Proctor, N.S. and P.J. Lynch. 1993. Manual of ornithology: avian structure and function. Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CN.

Rabenold, K.N. 1993. Latitudinal gradients in avian species diversity and the role of long-distance migration. Current Ornithology 10:247-274.

Ritchie, J.C. 1982. Postglacial vegetation of Canada. Cambridge University Press, Oxford.

Selander, R.K. 1971. Systematics and speciation in birds. Pp. 57-147 in Avian Biology, vol. 1 (D.S. Farner and J.R. King, eds.). Academic Press, New York, NY.

Sibley, C.G. and J.E. Ahlquist. 1985. The phylogeny and classification of the Australo-Papuan passerine birds. Emu 85:1-14.

Tallis, J. 1990. Climate Change and Plant Communities. Academic Press, London.

Watson, D. M. 2005. Diagnosable versus Distinct: Evaluating Species Limits in Birds. BioScience 55: 60-68.

Wiens, J.A. 1991. Distribution. Pp. 156-174 in The Cambridge Encylopedia of Ornithology (M. Brooke and T. Birkhead, eds.). Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, NY.

Welty, J.C. and L. Baptista. 1988. The life of birds, 4th ed. Saunders College Publishing, New York, NY.

Willson, M.F. 1976. The breeding distribution of North American migrant birds: a critique of MacArthur (1959). Wilson Bulletin 88:582-587.

Useful links:

Geography and Ecology of Species Distributions

Glaciers may not have driven modern bird evolution