| BIO 554/754

Ornithology Nervous System: Brain & Senses |

See The Bird in Black |

| BIO 554/754

Ornithology Nervous System: Brain & Senses |

See The Bird in Black |

The Avian Nervous System consists of

Seminar - Manakins (Aves: Pipridae): do you want to dance? by Betty Loiselle

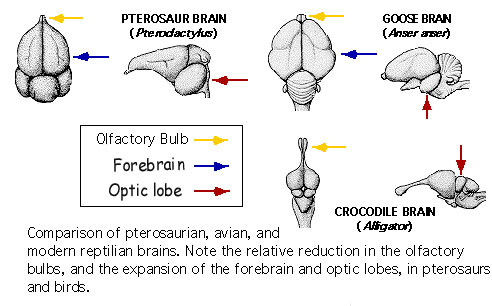

Due to common ancestry, the brains of reptiles & birds are similar. However, birds have relatively larger cerebral hemispheres & cerebella. In addition, birds have larger optic lobes & smaller olfactory bulbs (Husband and Shimizu 1999).

The avian brain includes:

|

Neuroanatomy of a Rock Pigeon brain. A) Dorsal view of a whole brain with key regions labeled: hyperpallium (H), mesopallium (M),

and arcopallium (A). B) Ventral view showing eight main anatomical components. C, D, Mid-sagittal sections showing cross-sectional anatomy,

with detailed annotations corresponding to structures identified in panel B (From: Shan et al. 2025).

Random Act of Anatomy - bird & dinosaur brains

Random Act of Anatomy - turkey brain endocast

Sharp-shinned Hawk skull and brain

Wood Stork skull and brain

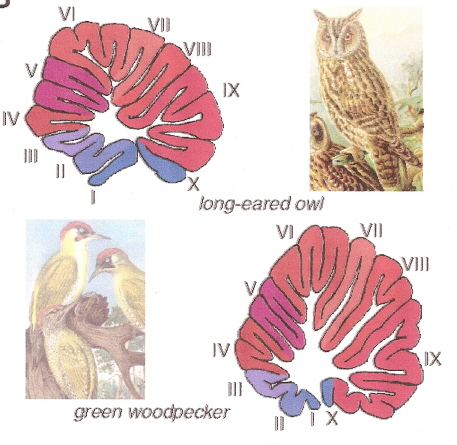

Woodpeckers, corvids, and parrots have longer, larger cerebellar lobes IV, VI, VII, VIII, and IX than many other birds.

These areas of the cerebellum help coordinate visual and beak-related movements, and woodpeckers, corvids, and parrots

are generally very adept when it comes to using their beaks and.or tongues to manipulate and explore external objects.

Surprisingly, birds that are excellent flyers, e.g., swifts and falcons, do not have unusually large cerebellums, suggesting that well-developed

motor skills do not require an increase in cerebellum size (Sultan 2005).

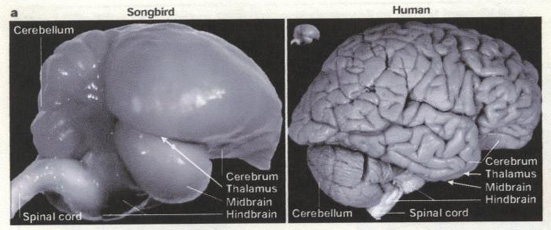

Side views of Zebra Finch & human brains. Inset

(next to human brain) is the

Zebra Finch brain to the same scale (From: Jarvis et

al. 2005).

Bird brains (Nova - Science Now)

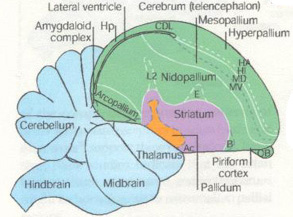

| Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate

brain evolution -- A consortium of neuroscientists (Jarvis et al. 2005)

has proposed a renaming of the structures of the bird brain to correctly

portray birds as more comparable to mammals in their cognitive ability.

The scientists assert that the century-old traditional nomenclature is

outdated and does not reflect new studies that reveal the brainpower of

birds. "We believe that names have a powerful influence on the experiments

we do and the way in which we think," wrote the consortium members. "For

this reason, (we have) reconsidered the 100-year-old terminology used to

describe the avian cerebrum. Our current understanding of the avian brain

requires a new terminology that better reflects these functions and the

homologies between avian and mammalian brains." The old terminology --

which implied that the avian brain was more primitive than the mammalian

brain -- has hindered scientific understanding.

The revised nomenclature for avian brains is aimed at replacing the system developed in the 19th century by Ludwig Edinger, the father of comparative neuroanatomy. Edinger used prefixes such as palaeo- ("oldest") and archi- ("archaic") to designate structures in the avian brain and neo- ("new") to designate supposedly new structures, particularly in the mammalian brain. "According to this theory, the avian cerebrum is almost entirely composed of basal ganglia, a structure involved only in instinctive behavior, and the malleable behavior thought to typify mammals exclusively requires the so-called neocortex," wrote the researchers. However, "We have to get rid of the idea that mammals -- and humans in particular -- are the pinnacle of evolution. We also have to understand that evolution is not linear, but an intricate branching process. So, we can't automatically expect to track a structure in the human brain back to other current vertebrate species."

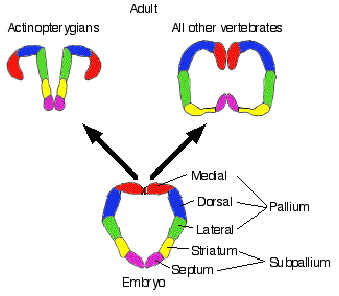

Jarvis et al. (2005) describe studies demonstrating that so-called "primitive" regions of avian brains are sophisticated processing regions homologous to those in mammals. These regions carry out sensory processing, motor control and sensorimotor learning just as the mammalian neocortex. Studies have also shown that the avian and mammalian brain regions are comparable in their genetic and biochemical machinery. The neocortex and related areas in the mammalian brain are derived from a region in the embryonic cerebrum called the pallium, which means mantle or covering. Edinger thought, however, that most of this region in the bird cerebrum was part of the basal ganglia. Accordingly, he gave them names that ended in the basal ganglia term “-striatum”, a practice he also employed in naming the parts of the mammalian basal ganglia. As a result of the recent studies, the consortium recommends such changes as renaming the avian brain region called the "archistriatum" as the "arcopallium," (arched pallium); and renaming the region that includes part of the true basal ganglia in birds, the "palaeostriatum primitivum" and the "ventral palaeostriatum" which sits below the pallium as the "pallidum" (pallidal or pale domain).

Jarvis pointed out that "there were people in the field of avian neurobiology who knew the real structures behind these names and knew the names were wrong." For example, researchers not familiar with studies demonstrating the sophistication of the avian brain could not understand how birds could exhibit sophisticated cognitive abilities with brains that held only what the nomenclature designated as the equivalent of the human basal ganglia. This new nomenclature will help people understand that evolution has created more than one way to generate complex behavior -- the mammal way and the bird way. And they're comparable to one another. In fact, some birds have evolved cognitive abilities that are far more complex than in many mammals." |

The cerebral hemispheres of birds, like those of other vertebrates,

consists of 2 regions:

All vertebrates have a cerebrum based on the same basic plan; major phylogenetic

changes are due to loss, fusion, or enlargement of the various regions.

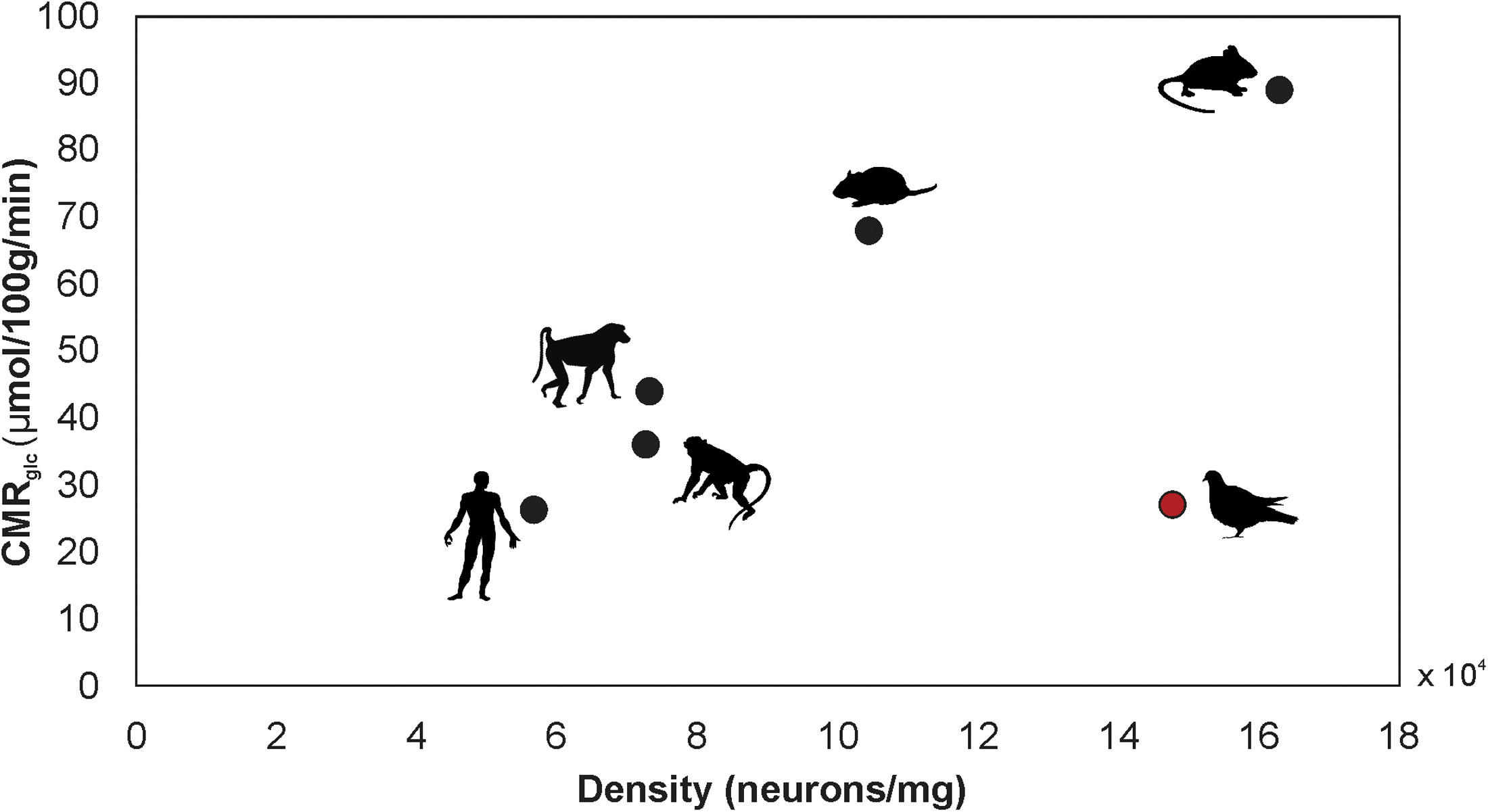

Scaling of mean-specific CMRglc (cerebral metabolic rate of glucose consumption) and neuron density in the whole brains of several species of mammals and Rock Pigeons.

Neurons in the brains of pigeons consume glucose at a rate approximately 3 times lower than that of the average mammalian neuron. This remarkably low neuronal energy budget explains how pigeons, and possibly other avian species, can support such high numbers

of neurons without associated metabolic costs or compromising neuronal signaling. The advantage in neuronal processing of information at a higher efficiency possibly emerged during the distinct evolution of the avian brain (From: von Eugen et al. 2022).

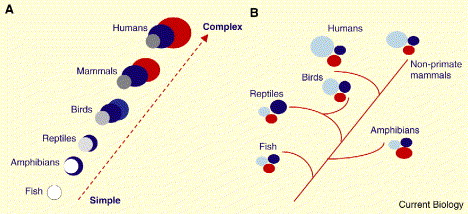

Schematic representation of two theories of brain evolution. (A) The outdated ‘scala naturae’ theory, where evolution occurs in a linear, progressive fashion up a ladder in which ‘lower’ (simple) species evolve into ‘higher’ (complex) species; going from fish and amphibians at the bottom through reptiles and birds to primates and humans at the top. With respect to brain evolution, the increasing complexity resulting from climbing the ladder leads to the appearance of completely new areas which are then added onto old ones. Each colour represents a different hypothetical brain region, either old or new. (B) The modern theory, where evolution is tree-like and new species evolve from older ancestral forms. With respect to brain evolution, complexity is derived from refining neural structures which are already present in ancestral forms, such that brain regions increase in size. There are no truly new brain areas, only elaborations of established regions. The colors represent different brain regions, but rather than new areas being added, evolutionarily old areas are increased or decreased in size (or complexity) (From: Emery and Clayton 2005).

Source: http://www.auburn.edu/academic/classes/zy/0301/Topic19/Topic19.html

Schematic showing the organization of a sensory system

in the bird/reptilian telencephalon (A) and the location

of the homologous neurons in the mammalian cortex (B).

The avian telencephalon has only a thin lateral cortex, and

a prominent protrusion into the lateral ventricle (V),

the dorsal ventricular ridge (DVR). The dorsal ventricular ridge contains

several different neuronal populations, directly corresponding

to those found in different layers of the mammalian neocortex,

including thalamic recipient neurons, interneurons, and

descending projections that leave the cortex to contact brainstem

and spinal cord neurons. The dorsal ventricular ridge

protrudes into the ventricle of birds and reptiles, and hence for

many years was erroneously thought to be homologous to

the mammalian basal ganglia (BG). In mammals (B),

homologous populations of neurons are found within distinct

layers of the cortex. The striking similarities in basic neuronal

properties and circuits in reptiles, birds, and mammals

led to the proposal that the specific neurons evolved prior to the

evolutionary appearance of mammalian cortex. Hp, hippocampus

(Karten 1997).

Increasing sophistication in sensory processes, motor control, and behavior in reptiles and, particularly, birds over evolutionary time may have been the selective force driving the development & increasing volume of the avian pallium. The basic function of the pallium is to serve as a linkage between sensory inputs and motor outputs; an interface between sensory and perceptual processing and mechanisms which modulate behavior. This is also the basic function of the mammalian cortex.

|

Schematic summary comparing the neuronal circuitry of auditory pathways in the dorsal ventricular ridge of the avian telencephalon and the equivalent neocortical circuit of the mammalian auditory cortex. In the avian forebrain, the populations of neurons corresponding to the individual layers of mammalian cortex are organized as clusters, rather than layers. This circuit in the mammal is represented as a simplified three-layered cortex, consisting of a layer of thalamic recipient neurons (receiving sensory input; blue) forming layer IV, a group of interneurons (yellow) forming the more superficial layers, and a group of descending motor neurons (DTEs) (red), the output neurons of this cortical region, forming layers V and VI. The morphology of individual neurons, their transmitters, and physiological properties at each parallel step of the circuit are virtually identical in bird dorsal ventricular ridge and mammalian cortex (Karten 1997). |

Food-caching chickadees rely on spatial cognition to recover numerous food caches to survive winters in harsh environments with severe winters. Chickadees wintering in harsher environments are known to have better spatial cognition associated with greater reliance on food caches for survival, and Sonnenberg et al. (2019) provided the first evidence of natural selection on spatial cognition in food-caching Mountain Chickadees at high elevations in the Sierra Nevada (US) by showing that (1) adult chickadees performed better than juveniles in spatial cognitive tasks, (2) spatial cognitive performance was not significantly different between years in the same chickadees tested in their first year of life and after surviving to their second winter, and (3) individual variation in spatial cognitive abilities was associated with differences in survival.

Individual variation in spatial cognition among Mountain Chickadees is associated with variation across the genome, with top outlier genes associated with hippocampal development and function. Mountain Chickadees are non-migratory birds that use spatial learning and memory to relocate their food stores and survive harsh winters.

Check out the paper at https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)01425-1.

In general, the cognitive abilities of birds are increasingly appreciated as more complex than presumed several years ago. For example, as listed by Jarvis et al. (2005):

So, many birds have cognitive abilities that are quite sophisticated, and

some birds and mammals have cognitive abilities that clearly exceed those

of all other birds and mammals.

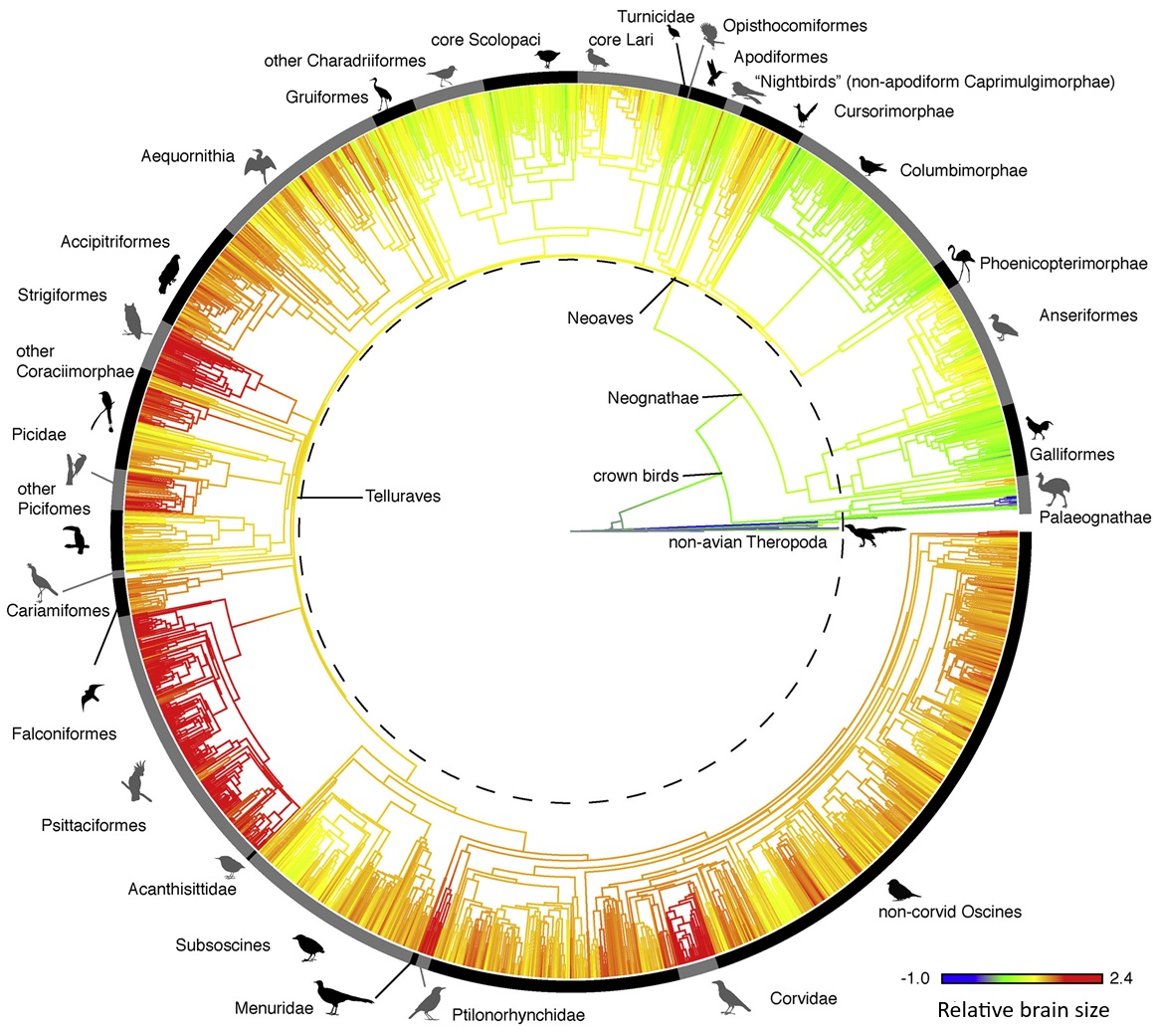

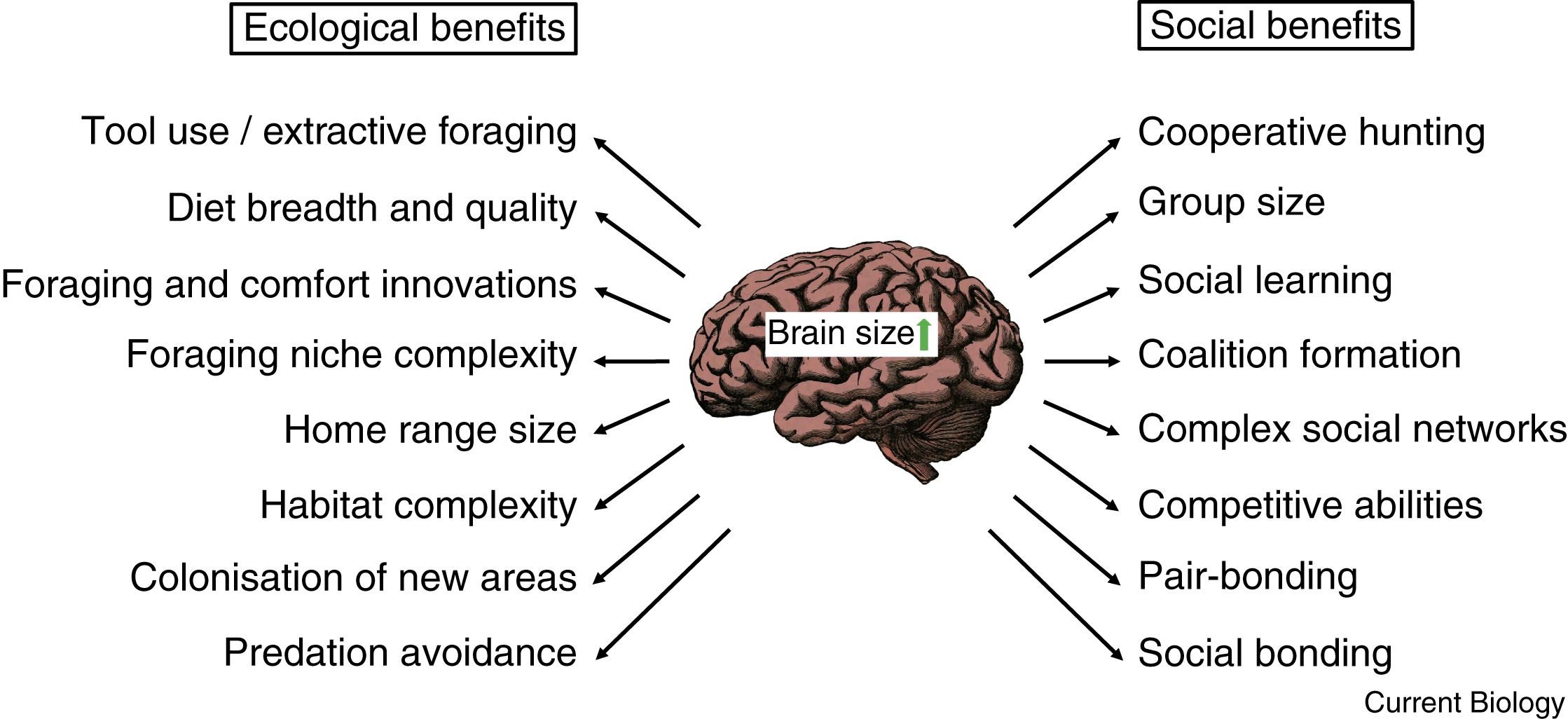

Brains are metabolically expensive to develop and maintain. So why has evolution favored such a costly organ in

some birds and mammals? LIkely because of the many potential benefits large brains provide. With brain size used as a proxy

for cognitive performance or intelligence, larger-brained and thus more intelligent species profit from a wide range of both ecological

and social benefits (From: Heldstab et al. 2022).

New Caledonian Crow

Click on the photo to see a short video clip from

"The Life of Birds" - New Caledonian Crows

Green Heron - using bait to capture fish

|

Magpies exhibit self-recognition -- Comparative studies suggest that at least some bird species have evolved mental skills similar to those found in humans and apes. This is indicated by feats such as tool use, episodic-like memory, and the ability to use one's own experience in predicting the behavior of conspecifics. It is, however, not yet clear whether these skills are accompanied by an understanding of the self. In apes, self-directed behavior in response to a mirror has been taken as evidence of self-recognition. Prior et al. (2008) investigated mirror-induced behavior in European Magpies. Magpies are corvids (order Passeriformes), a phylogenetic group characterized by large brains relative to body weight. The relative brain size of passerines is similar to primates in allometric analyses and, among passerines, corvids stand out with particular high relative brain size. Thus, magpies belong to a group of animals with very high relative brain size As in apes, some individuals behaved in front of the mirror as if they were testing behavioral contingencies. When provided with a mark (see photo below), magpies showed spontaneous mark-directed behavior. These findings provide the first evidence of mirror self-recognition in a non-mammalian species, and suggest that essential components of human self-recognition have evolved independently in different vertebrate classes with a separate evolutionary history and that a laminated (layered) cortex is not a prerequisite for self-recognition.

|

New Caledonian Crows can use tools to manipulate other tools.

This one is using a small stick to obtain a larger stick that, in turn, is used to obtain food.

Metatool use by New Caledonian Crows -- A crucial stage in hominin evolution was the development of metatool use—the ability to use one tool on another. Although the great apes can solve metatool tasks, monkeys have been less successful. Taylor et al. (2007) provided experimental evidence that New Caledonian crows can spontaneously solve a demanding metatool task where a short tool is used to extract a longer tool that can then be used to obtain meat. Six of seven crows initially attempted to extract the long tool with the short tool. Four successfully obtained meat on the first trial. The experiments revealed that the crows did not solve the metatool task by trial-and-error learning during the task or through a previously learned rule. The sophisticated physical cognition shown appears to have been based on analogical reasoning. The ability to reason analogically may explain the exceptional tool-manufacturing skills of New Caledonian Crows.

The position of caching trays is shown in Compartments A and C, and of the food bowl in Compartment B.

Dotted lines represent the compartmental divisions, although during caching no dividers were in place. In the second experiment,

the compartmental layout was the same except that two food bowls, equidistant from compartments A and C, were used.

Scrub-jays plan ahead -- In the evening, jays were kept in the middle section, and fed powdered pine nuts that they couldn't store. In the morning, they were kept either in the 'breakfast room', where they were given food, or went hungry in the 'no-breakfast room'.

After getting used to this set-up, the jays were given whole pine nuts in the evening that they could bury in trays of sand. The jays put three times as many in the no-breakfast room than in the breakfast room, so that they wouldn't go hungry in the morning.

In a second experiment, the jays got breakfast in both rooms. However, their breakfast comprised whole peanuts in one room, and dried dog food in the other. When given both foods in the evening, the birds stored each food in the room where it would be lacking the next morning.

Planning for the future by Western Scrub-Jays -- Knowledge of and planning for the future is a complex skill that is considered by many to be uniquely human. We are not born with it; children develop a sense of the future at around the age of two and some planning ability by only the age of four to five. Raby et al. (2007) performed experiments to test whether Western Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma californica) plan for the future. They showed that the jays plan for future needs, both by preferentially caching food in a place in which they have learned that they will be hungry the following morning and by differentially storing a particular food in a place in which that type of food will not be available the next morning. Although some primates and corvids take actions now that are based on their future consequences, these have not been shown to be selected with reference to future motivational states, or without extensive reinforcement of the anticipatory act. The results described here suggest that the jays can spontaneously plan for tomorrow without reference to their current motivational state, thereby challenging the idea that this is a uniquely human ability.

Parental provisioning drives brain size in birds -- Large brains support numerous cognitive adaptations and therefore may appear to be highly beneficial. Nonetheless, the high energetic costs of brain tissue may have prevented the evolution of large brains in many species. This problem may also have a developmental dimension: juveniles, with their immature and therefore poorly performing brains, would face a major energetic hurdle if they were to pay for the construction of their own brain, especially in larger-brained species. Griesser et al. (2023) examined the possible role of parental provisioning for the development and evolution of adult brain size in birds. A comparative analysis of 1,176 bird species revealed that various measures of parental provisioning (precocial vs. altricial state at hatching, relative egg mass, time spent provisioning the young) strongly predict relative brain size across species. The parental provisioning hypothesis also provides an explanation for the well-documented that altricial birds have larger brains than precocial ones. These authors, therefore, concluded that the evolution of parental provisioning allowed species to overcome the seemingly insurmountable energetic constraint on growing large brains, which in turn enabled bird species to increase survival and population stability. Because including adult eco- and socio-cognitive predictors only marginally improved the explanatory value of our models, these findings also suggest that the traditionally assessed cognitive abilities largely support successful parental provisioning. These results therefore indicate that the cognitive adaptations underlying successful parental provisioning also provide the behavioral flexibility facilitating reproductive success and survival. |

Intelligent crow

Bird Brains Like Human Brains: Episodic Memory Processes

Similar - Birds can remember not only where, but when, they hid food

items & even dig up less perishable food if too much time has passed

& their favorite worms have probably rotted (Clayton and  Dickinson 1998). The study of Scrub Jays (Aphelocoma californica)

marks the first demonstration of episodic, or event-based, memory in animals

other than humans. This type of memory is referred to as “mental time travel”

because it involves mental images of past events. To remember where you

put your car keys, you might “see” yourself walking into the house the

night before & placing the keys on a table. Previous work had shown

that birds can remember what kind of food they had stored & where they

had hidden it, even without sensory clues like smell & appearance.

But making decisions based on the timing of past events is crucial to episodic

memory. In the study, N. S. Clayton (Univ. of California-Davis) &

Anthony Dickinson (Cambridge Univ.) allowed Scrub Jays to store their favorite

food (wax worms) on one side of a sand-filled tray & peanuts on the

other side. Jays retrieved the wax worms if less than four hours old, but

birds that had learned that wax worms decompose avoided older worms in

favor of peanuts.

Dickinson 1998). The study of Scrub Jays (Aphelocoma californica)

marks the first demonstration of episodic, or event-based, memory in animals

other than humans. This type of memory is referred to as “mental time travel”

because it involves mental images of past events. To remember where you

put your car keys, you might “see” yourself walking into the house the

night before & placing the keys on a table. Previous work had shown

that birds can remember what kind of food they had stored & where they

had hidden it, even without sensory clues like smell & appearance.

But making decisions based on the timing of past events is crucial to episodic

memory. In the study, N. S. Clayton (Univ. of California-Davis) &

Anthony Dickinson (Cambridge Univ.) allowed Scrub Jays to store their favorite

food (wax worms) on one side of a sand-filled tray & peanuts on the

other side. Jays retrieved the wax worms if less than four hours old, but

birds that had learned that wax worms decompose avoided older worms in

favor of peanuts. |

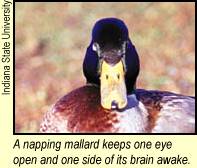

Half-asleep birds choose which half dozes - Birds

that are literally half-asleep - with one brain hemisphere alert & the other snoozing - control which side of the brain remains awake. The

brain hemispheres take turns sinking into the sleep stage characterized

by slow brain waves. The eye controlled by the sleeping hemisphere shuts,

while the wakeful  hemisphere's

eye stays open and vigilant. Birds also can sleep with both hemispheres

resting at once. To check whether birds can control half-brain sleeping,

Rattenborg et al. (1999) monitored rows of Mallards napping. Decades of studies of

bird flocks led researchers to predict extra vigilance in the more vulnerable,

end-of-the-row sleepers. Sure enough, the end birds tended to keep open

the eye on the side away from their buddies. Mallards in the

inner spots showed no preference for gaze direction. Also, birds dozing

at the end of the line resorted to single-hemisphere sleep, rather than

total relaxation, more often than inner ducks did. Rotating 16 birds through

the positions in a four-duck row, the researchers found outer birds half-asleep

during some 32% of snoozing time versus about 12% for birds in internal

spots. "We believe this is the first evidence for an animal behaviorally

controlling sleep and wakefulness simultaneously in different regions of

the brain," the researchers said. The results provide the best evidence

yet for a long-standing conjecture that single-hemisphere sleep evolved

as creatures scanned for predators. The preference for opening an eye on

the lookout side could be widespread. Useful as half-sleeping might be,

it's only been found in birds and such aquatic mammals as dolphins, whales,

seals, and manatees. Presumably, keeping one side of the brain awake allows

a sleeping animal to surface occasionally to avoid drowning, explained Rattenborg. hemisphere's

eye stays open and vigilant. Birds also can sleep with both hemispheres

resting at once. To check whether birds can control half-brain sleeping,

Rattenborg et al. (1999) monitored rows of Mallards napping. Decades of studies of

bird flocks led researchers to predict extra vigilance in the more vulnerable,

end-of-the-row sleepers. Sure enough, the end birds tended to keep open

the eye on the side away from their buddies. Mallards in the

inner spots showed no preference for gaze direction. Also, birds dozing

at the end of the line resorted to single-hemisphere sleep, rather than

total relaxation, more often than inner ducks did. Rotating 16 birds through

the positions in a four-duck row, the researchers found outer birds half-asleep

during some 32% of snoozing time versus about 12% for birds in internal

spots. "We believe this is the first evidence for an animal behaviorally

controlling sleep and wakefulness simultaneously in different regions of

the brain," the researchers said. The results provide the best evidence

yet for a long-standing conjecture that single-hemisphere sleep evolved

as creatures scanned for predators. The preference for opening an eye on

the lookout side could be widespread. Useful as half-sleeping might be,

it's only been found in birds and such aquatic mammals as dolphins, whales,

seals, and manatees. Presumably, keeping one side of the brain awake allows

a sleeping animal to surface occasionally to avoid drowning, explained Rattenborg. |

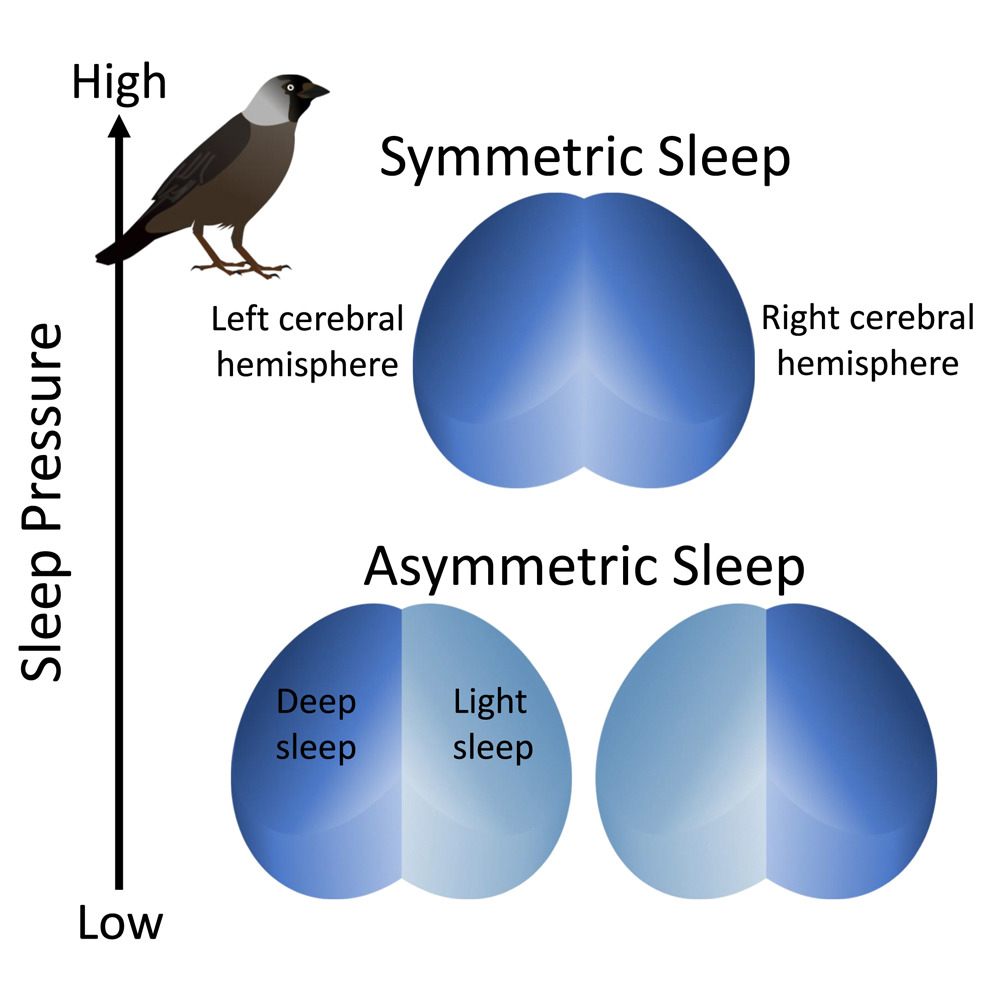

With increasing sleep pressure (i.e., increased need for sleep), bird can switch

from asymmetric sleep to symmetric sleep (From: van Hasselt et al. 2025).

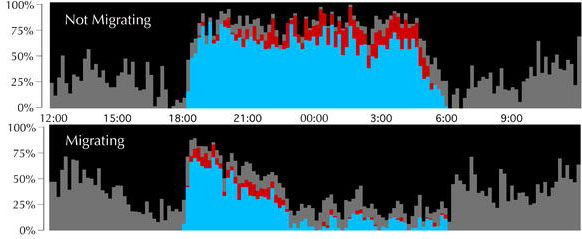

Proportion of time in each behavioral state for nonmigrating (top) and migrating (bottom) birds. The proportion of every 10-min period spent in each sleep/wakefulness state was averaged for all birds: wakefulness (black), drowsiness (gray), slow-wave sleep (blue), and REM sleep (red). Note that overall sleep propensity in migrating birds is greatly diminished between about 22:30 and 06:00. Note also the increased propensity for REM sleep from 18:00 to 20:00 as compared to the same time period when not migrating. No rest for the weary? -- Every spring and fall,

billions of songbirds fly thousands of miles between their summer breeding

grounds and their wintering grounds in Mexico, and Central and South America.

While some birds fly during the day, most fly at night. The migratory pace

of most birds—as well as the increased activity required to sustain migrations—suggests

little time for sleep. Yet field observations indicate that presumably

sleep-deprived fliers appear no worse for wear, foraging, navigating, and

avoiding predators with aplomb. How do songbirds cope with so little sleep?

|

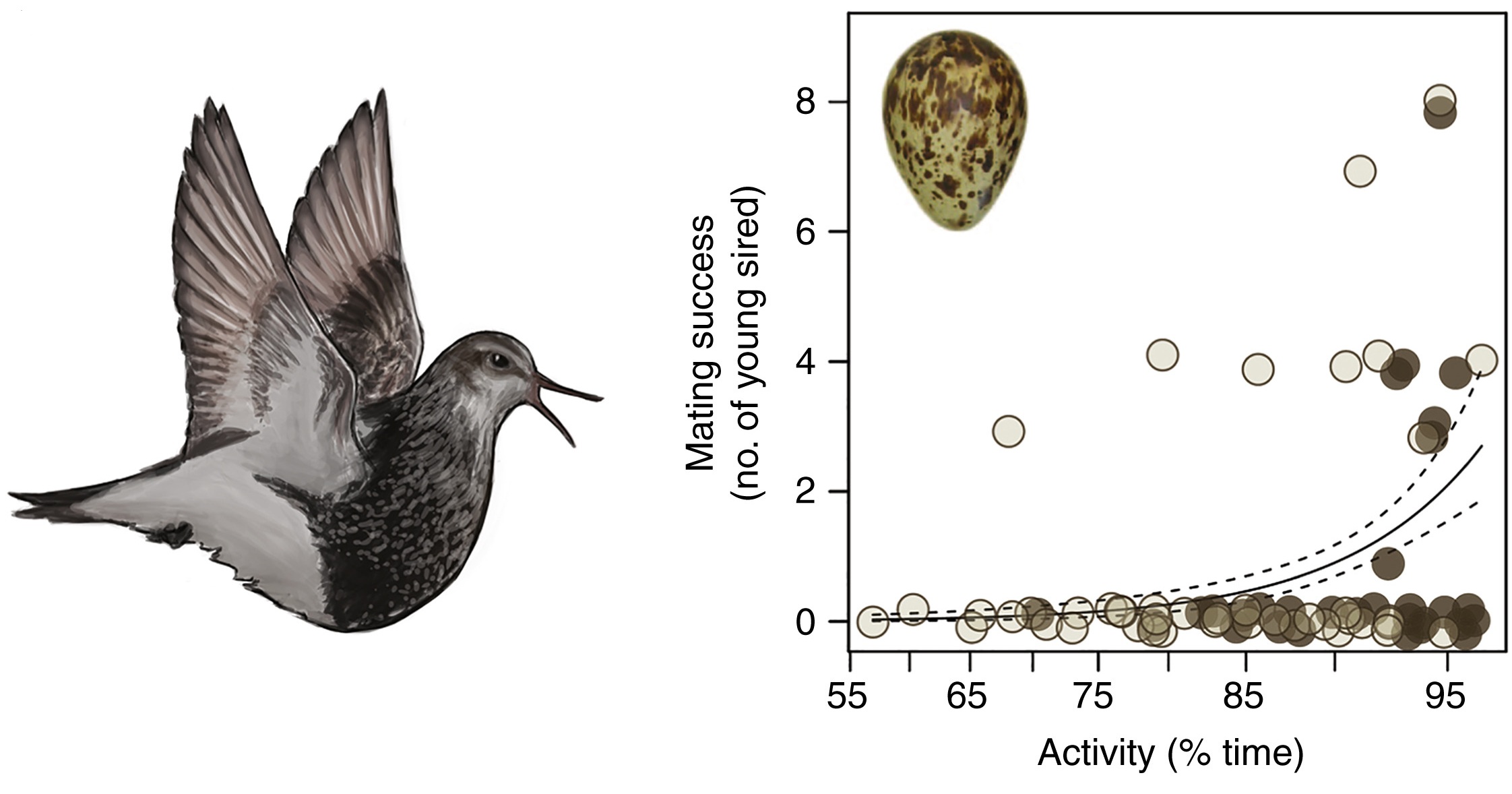

For Pectoral Sandpipers breeding in Alaska, males that sleep the least sire the most offspring (From: Lesku and Schmidt 2022).

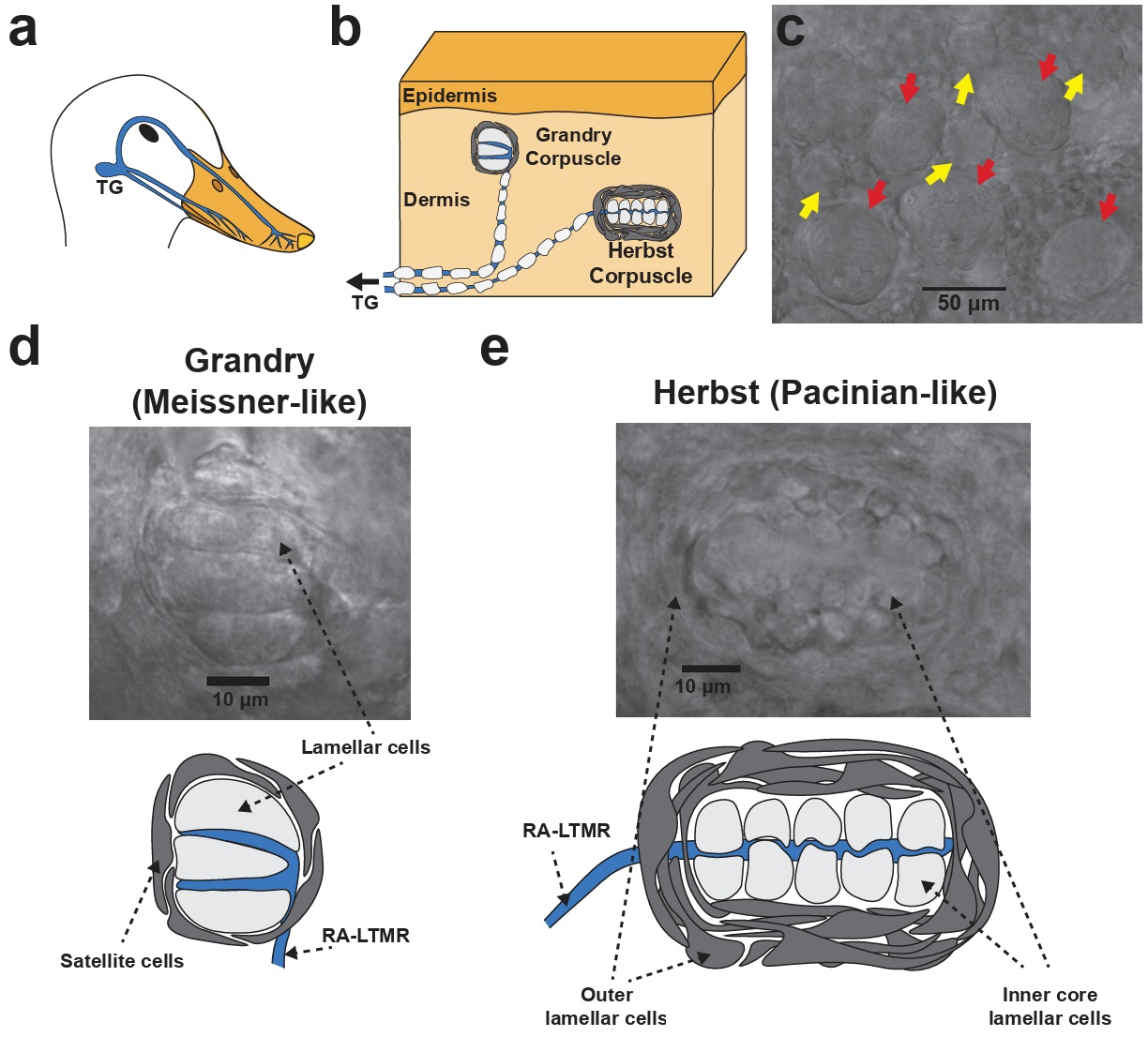

Tactile organs - touch receptors (Herbst corpuscles, which are similar to Pacinian corpuscles) are abundant in the bills of some birds, such as waterfowl & shorebirds, & in the tongues of other birds, such as woodpeckers. Additional touch/pressure receptors (Merkel cells) are found in the dermis (skin) of birds.

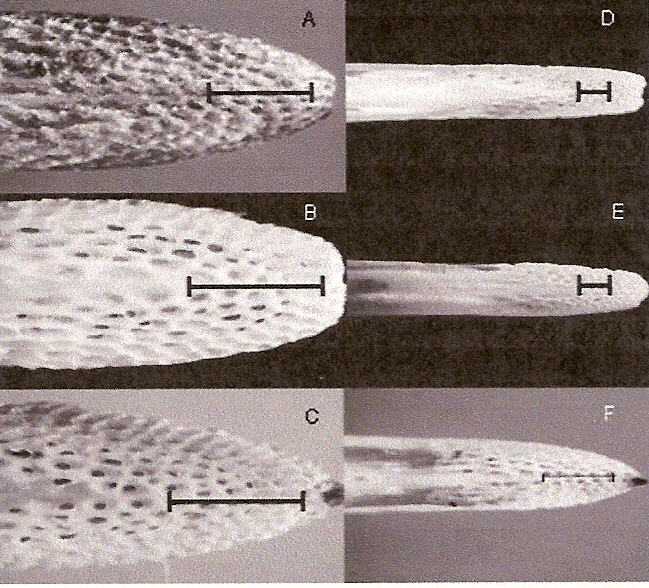

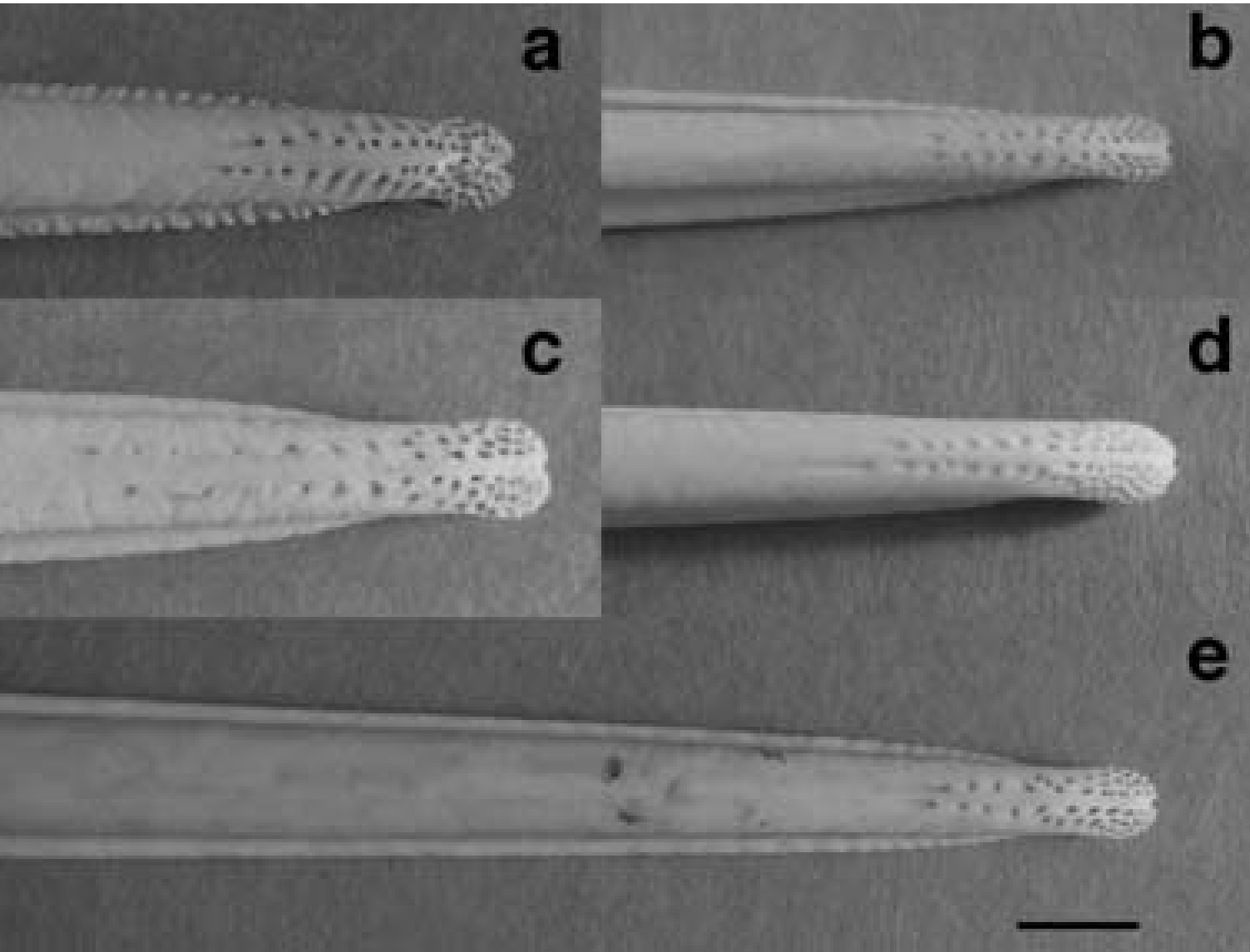

Sensory pits in the upper and lower bill of a female Western Sandpiper (A, lower bill and B, upper bill),

male Western Sandpiper (C, lower bill), female Dunlin (D, lower bill), male Dunlin (E, upper bill), and male

Least Sandpiper (F, upper bill). The scale indicates 1 mm. The skin has been removed and bills were soaked in

bleach to

dissolve the remaining soft tissue and expose the pits. Herbst corpuscles are found in high densities in

these sensory pits (Nebel et al. 2005).

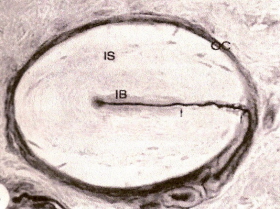

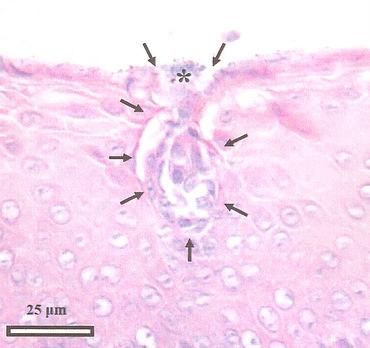

Herbst corpuscle from a duck's bill. OC, outer capsule; IB, inner bulb; IS, inner space; dark line = neuron. Magnified 600x (Saxon 1996). |

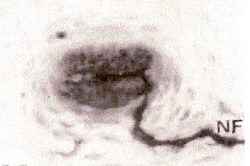

Grandry corpuscle from duck's bill. NF, nerve fiber. Two Grandry cells, one on each side of the neuron. Magnified 1000x (Saxon 1996). |

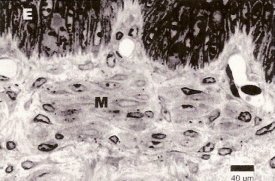

Cross-section through quail beak skin. In the dermis, below the epidermis (E), numerous Merkel cells (M) with nerve terminals are visible (From: Halata et al. 2003).. |

Cross-section showing two twin-groups of Merkel nerve endings from the tarsometatarsal skin of a quail. K, keratinocyte; M, Merkel cells with cytoplasmic protrusions (arrows), T, nerve terminals; S, terminal Schwann cells (From: Halata et al. 2003). |

Structure of Grandry and Herbst corpuscles in the mechanosensory bill of waterfowl. (a) The neuroanatomy underlying tactile sensation in the bill.

Low threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) from the trigeminal ganglia (TG) project to the skin of the bill. (b) Trigeminal LTMRs form terminal end-organs

in the bill dermis, most of which are Grandry and Herbst corpuscles. (c) Image of the bill dermis under a brightfield microscope. Grandry (yellow arrows)

and Herbst (red arrows) corpuscles are present at a cumulative density of up to 200 corpuscles per square millimeter of skin. (d) Higher magnification image

and diagram of a Grandry corpuscle. A Grandry corpuscle is composed of 2-12 lamellar cells that are layered above and below the terminals of the Rapidly-adapting

LTMR. The structure is surrounded by satellite cells. (e) Higher magnification image and diagram of a Herbst corpuscle. A Herbst corpuscle is composed of an

outer capsule formed by outer core lamellar cells that enclose an inner core consisting of inner core lamellar cells. The outer core and inner core lamellar

cells form concentric lamellae surrounding the mechanoreceptor afferent neuron (From: Ziolkowski et al. 2022).

Low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) are specialized sensory neurons that detect light, gentle touch, pressure, and vibration. They are highly sensitive, firing action potentials in response to minimal mechanical stimulation. Rapidly-adapting mechanoreceptors are sensory nerve endings that generate action potentials and nervous impulses only at the beginning and end of a stimulus, rather than during sustained pressure. They are specialized for detecting movement and vibration Lamellar cells are specialized, flattened, terminal glial cells forming concentric or stacked layers within Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles. Acting as non-neuronal mechanosensors, they detect high-frequency vibrations and pressure, playing an active role in mechanotransduction (i.e., converting mechanical stimuli like vibrations and pressure into nervous impulses). Satellite cells provide structural and metabolic support. Rapidly-adapting mechanoreceptors are sensory nerve endings that generate action potentials and nervous impulses only at the beginning and end of a stimulus, rather than during sustained pressure. They are specialized for detecting movement and vibration.

| Birds "Feel" Their Prey Under the Sand - Red Knots (Calidris canutus) can locate their favorite food (shellfish) in wet sand by inserting their beak half a centimeter into the sand for a few seconds (Piersma et al. 1998) This ability was demonstrated in experiments in which researchers hid small stones in the sand. Because stones do not send out any signals, the ability of Knots to detect them must be based on the sensitivity of their beaks to differences in currents in the water in wet sand between the individual grains, stones, or shells. Knots used in the experiments were unable to find hidden stones in dry sand. At the end of their beak, knots have clusters of 10 to 20 Herbst corpuscles that are sensitive to differences in pressure. When the bird sticks its sensitive beak into the sand at low tide, it produces a pressure wave because of the inertia of the water in the interstices between the particles. The pattern thus created betrays the presence of objects larger than the grains of sand. The rapid up-and-down movements of the bird's beak loosen the grains of sand, which then become packed together more tightly, displace the interstitial water, & cause the residual pressure around the object to increase. The nature of their localizing ability means that knots cannot distinguish between stones & shellfish in the sand, which is why they rarely look for food in areas where the sand contains stones, no matter how much shellfish could be found there. |

|

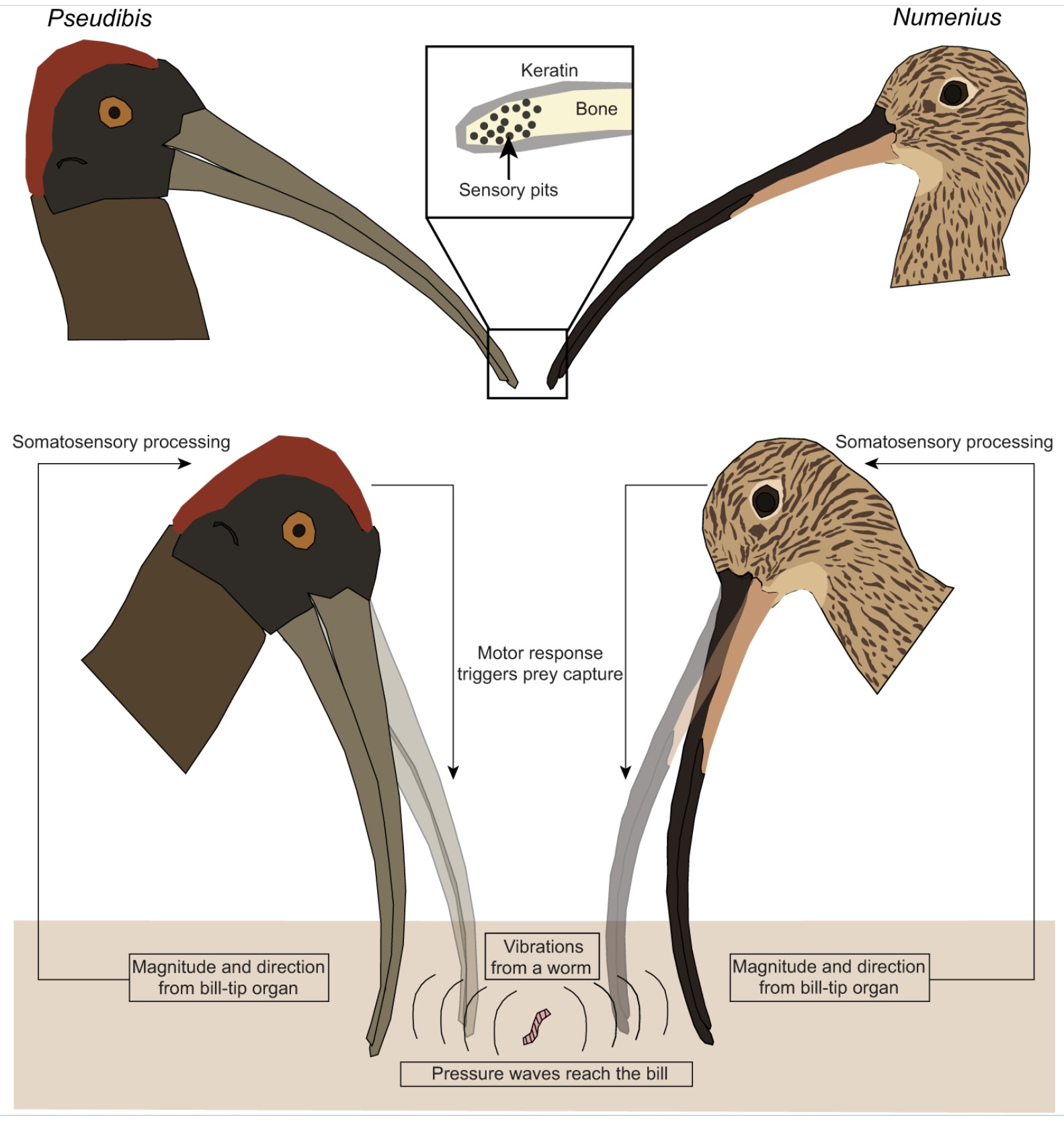

Bill sensory biomechanics. A Red-naped Ibis (Pseudibis papillosa) and a Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata)

each independently evolved a remote-touch bill-tip organ that can detect vibrations from a moving worm in a mud

substrate. Diverse bird groups use their bills to probe for invertebrates in soft mud or leaf litter, with mechanosensors

on the bill tip detecting pressure changes near or at the bill surface. In these species, foramina at the tip of the bony

portion of the bill contain sensors known as Herbst corpuscles organized into sensory pits. These sensors detect

pressure differences and vibrations that travel through substrates, and allow birds to locate wriggling worms or

other prey without direct contact. Ibises foraging in wetter substrates possess more pits with fewer Herbst

corpuscles in each, whereas species foraging in drier substrates possess fewer pits with more Herbst corpuscles

in each (From: Krishnan 2023).

Foraging Red Knots

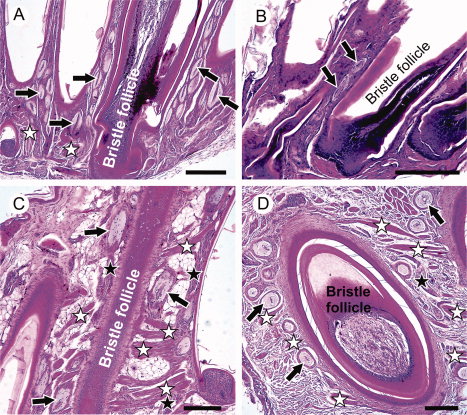

Facial bristle locations in five New Zealand bird species. (A) New Zealand Robin, Petroica australis; (B) Hihi, Notiomystis cincta; (C) New Zealand Fantail, Rhipidura fuliginosa; (D) Morepork, Ninox novaezealandae; (E) Brown Kiwi, Apteryx mantelli. Scale bars = 5 mm. |

Facial bristle follicles and associated Herbst corpuscles from four avian species: (A) New Zealand Robin; (B) New Zealand Fantail; (C) Morepork; (D) Brown Kiwi. Black arrows indicate examples of Herbst corpuscles; black stars indicate nerve bundles, white stars indicate muscles. |

Morphology, histology, and possible functions of facial bristles -- Knowledge of structure in biology may help inform hypotheses about function. Little is known about the histological structure or the function of avian facial bristle feathers. Cunningham et al. (2011) examined the morphology and histology, with inferences about function, of bristles in five predominantly insectivorous birds from New Zealand, including Brown Kiwi, Morepork, Hihi, New Zealand Robin, and New Zealand Fantail. Average bristle length corrected for body size was similar across species. Bristles occurred in distinct groups on different parts of the head and upper rictal bristles were generally longest. The lower rictal bristles of the fantail were the longest possessed by that species and were long compared to bristles of other species. Kiwis were the only species with forehead bristles, similar in length to the upper rictal bristles of other species, and the lower rictal bristles of fantails. Herbst corpuscles (vibration and pressure sensitive mechanoreceptors) were found in association with bristle follicles in all species. Nocturnal and hole-nesting birds had more heavily encapsulated corpuscles than diurnal open-nesting species. These results suggest that avian facial bristles generally have a tactile function in both nocturnal and diurnal species, perhaps playing a role in prey handling, gathering information during flight, navigating in nest cavities and on the ground at night, and possibly in prey-detection.

|

Filoplumes as feather-specific sensors. -- Birds are remarkably skillful in flight. Their execution of complex aerial maneuvers at high speeds suggests that they can quickly respond to forces detected through their feathers. But how do birds sense these forces on flight feathers given that feathers are keratinaceous structures lacking nerves? Almost certainly via unique mechanosensory feathers called filoplumes. Filoplumes resemble hairs with downy tufts at their tips (Figure to the left); the hair-like section corresponds to the rachis and the tuft is homologous to the barbs and barbules of typical feathers. Filoplumes grow from their own innervated follicle, and their nerves show peaks in the electrical activity of both slowly and rapidly adapting receptors when they or their companion feathers are moved outside of their typical orientation. Typical contour feathers have 1–2 associated filoplumes and flight feathers can have as many as 8–12 associated filoplumes. These observations suggest that filoplumes are well suited for detecting changes in the position of wing and tail feathers, which are essential for flight. In short, filoplumes appear to be complex sensors designed to detect subtle changes in the forces acting on their pennaceous feathers (Figures and text from: Rohwer et al. 2021).

|

Smell (olfaction):

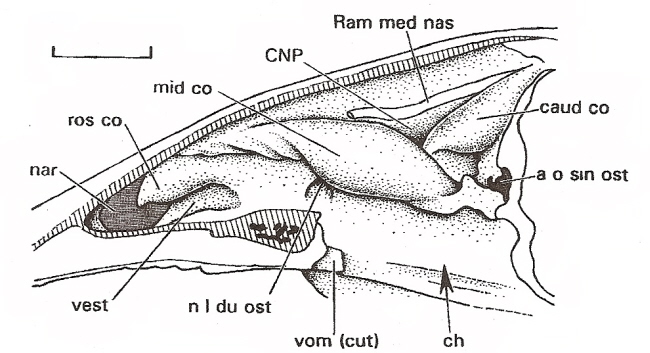

Nasal cavity of

a Mallard (scale bar = 1 cm). nar = naris, ros co = rostral concha, mid co = middle concha,

caud co = caudal concha, ch - choana (opening between nasal cavity and naspharynx), a o sin ost - ostium (openng into sinus cavity),

vest = nasal vestibule (anterior portion of nasal cavity), vom = vomer, Ram med nas = branch of ophthalmic nerve,

n l du ost = opening into lacrimal duct (Figure from Witmer 1995).

Turbinate bones (like those shown in the diagrams below) are

found in the caudal (olfactory) concha.

|

White-chinned Petrel |

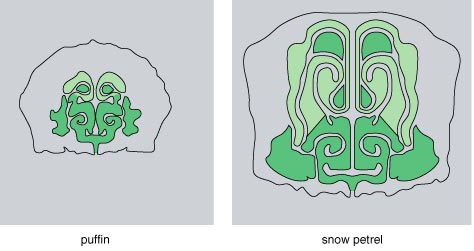

Anatomical features of procellariiforms indicate

that they should have a well-developed sense of smell. Within the complex

turbinate

structure of a Snow Petrel's nose (above), large amounts

of surface area are lined with olfactory epithelium, containing cells that

detect odor (light green). A puffin's nose is smaller

and has less olfactory epithelium. Procellariiforms are often called "tubenose"

seabirds because of the prominence of these structures,

seen clearly in a White-chinned Petrel’s profile (right). They also have

enlarged brain structures that process scents (Nevitt

1999)

|

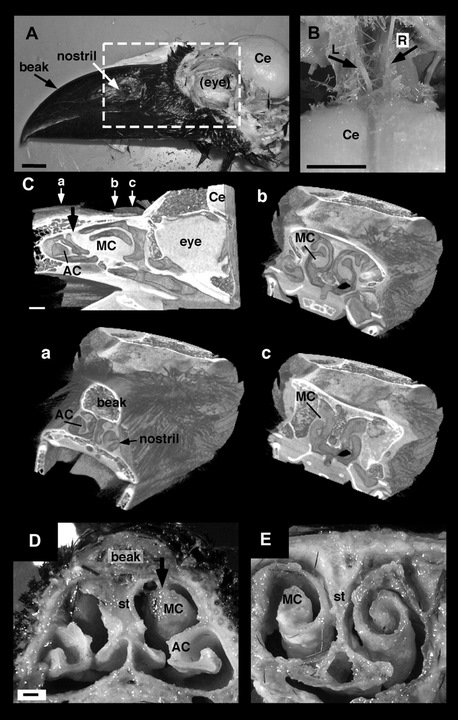

Nasal cavity of the Large-billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos). (A) Head of the Large-billed Crow (the cranial bone and eyeball have been removed). Bar = 10 mm. (B) The left and right olfactory nerve bundles independently project to the brain. L, left olfactory bundle; R, right olfactory bundle. Bar = 10 mm. (C) Sagittal and coronal 3-dimensional structural computed tomography (CT) images of the nasal cavity. The small white arrows (a–c) in the sagittal image indicate the positions through which the planes of the transverse CT images pass. Bar = 10 mm. (D and E) Transverse sections of the nasal cavity through the rostral end (D) and middle portion (E) of the maxillary conchae (MC). The bold black arrows in (C and D) indicate the rostral end of the MC. Bar in (D) = 1 mm. Ce, cerebrum; st, olfactory septum (From: Yokosuka et al. 2009). |

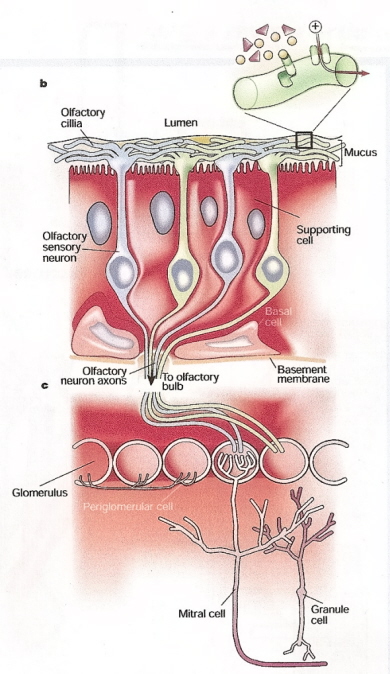

Olfactory sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium detect odors and conduct impulses to the olfactory bulb (mitral cells).

From the olfactory bulb, impulses travel other areas of the brain (olfactory tubercle) where odor is actually perceived (Figure

from: Firestein [2001]).

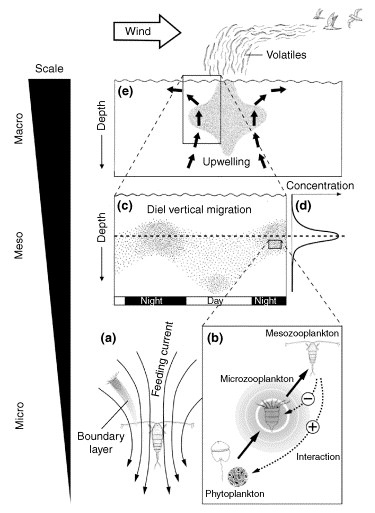

DMS and seabird foraging -- The function of DMS (dimethyl sulfide) and other volatile infochemicals in aquatic trophic interactions. (a) A suspension-feeding copepod (mesozooplankton) produces a feeding current that deforms the boundary layer at the surface of microzooplankton. This layer is enriched with infochemicals such as DMS (produced by bacteria metabolizing dead plankton). (b) The interaction between phyto- and microzooplankton produces more DMS and is represented by the circular shaded area around the microzooplankton. Such infochemicals are exploited by higher-order mesozooplankton when searching for microzooplankton prey. Dotted lines indicate the mode of the trophic interaction with negative effects on the microzooplankton and indirect positive effects for the phytoplankton. (c,d) The accumulation of infochemicals from microzooplankton prey (d) provides chemical cues to migrating mesozooplankton [individual dots in (c)]. (e) Local upwelling generates biological activity (dotted area) that increases the sea–air flux of DMS and other volatile infochemicals. The resulting chemical gradient serves as a directional cue to seabirds (Pohnert et al. 2007).

This video shows the movements of adult Galapagos Albatrosses making foraging trips to the west coast of South America during the breeding season in 2008. Along with the birds' movements, this animation also shows actual patterns of wind (arrows) and ocean chlorophyll (light green) during the same time. By comparing the animals' movements with environmental data like chlorophyll (which represents food availability), you can see why adultss fly so far to feed their young.

Strong winds reduce foraging success of albatrosses

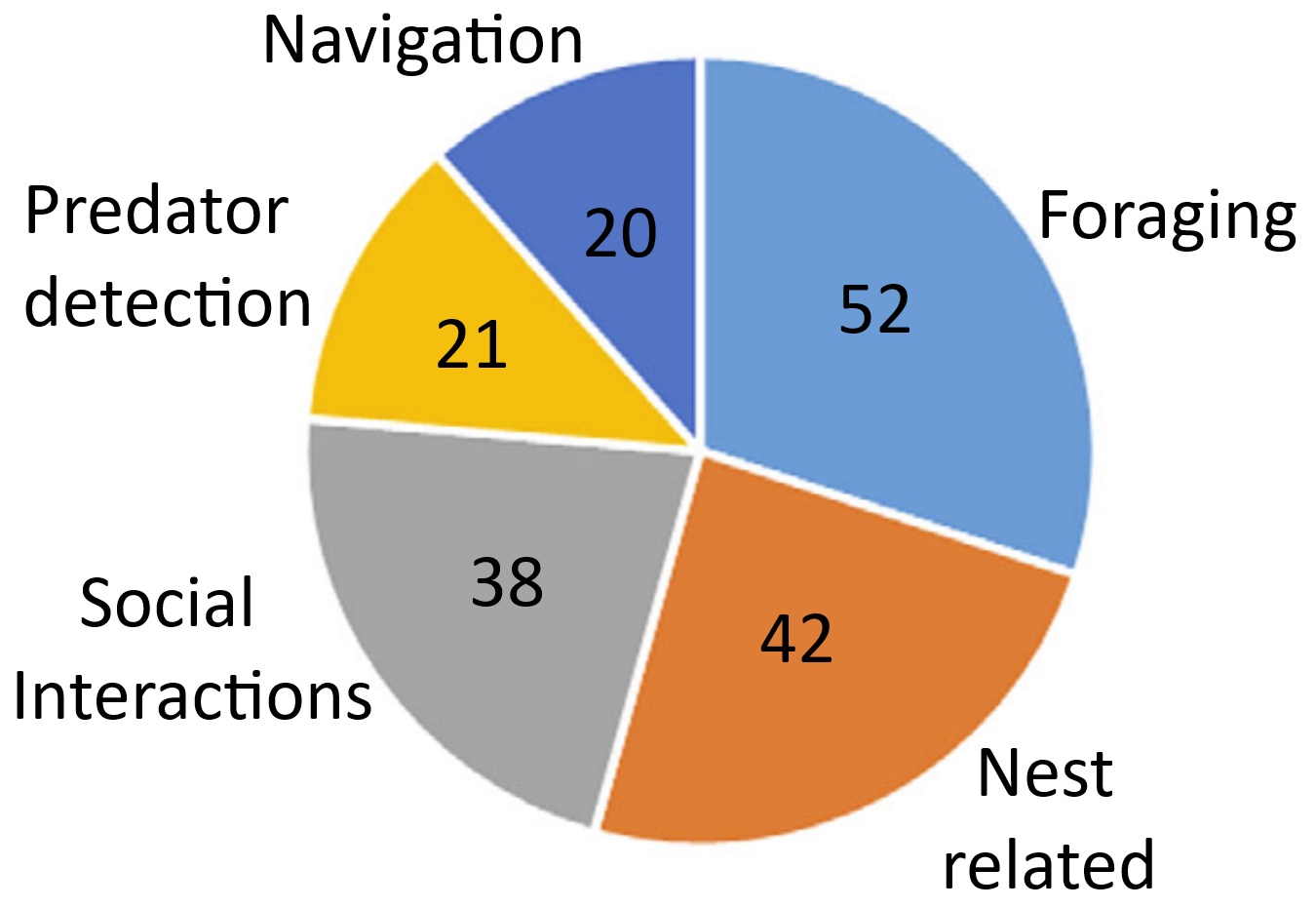

The number of studies testing experimentally how birds use their sense of smell during foraging,

nest-related behavior, social interactions, navigation, and predator detection. Some studies investigated olfaction in birds in a variety of contexts.

Several bird species use olfactory cues when locating specific food items, e.g., tube-nosed seabirds (Procellariiformes), Turkey Vultures, Greater Yellow-headed Vultures, Crested Caracaras, and Oriental Honey Buzzards. Few studies have shown that passerines use their sense of smell in foraging. Conclusive evidence is lacking concerning whether or not birds in the orders Psittaciformes and Piciformes use olfaction for foraging.

Few studies have investigated the role of olfaction in navigation in species other than the Domestic Pigeon, but it is likely that olfactory navigation is widespread in birds. For example, a study of radio-tracked migratory Gray Catbirds revealed that adult birds rendered anosmic could not orient in the same way as control adults. The role of olfaction in navigation has been

studied in several species of seabirds, mostly Procellariiformes. When displaced from their breeding colonies and released in the open ocean, Cory’s Shearwaters and Scopoli’s Shearwaters that were unable to smell were less likely to find their way back to their colonies. There is also evidence that Procellariiformes use olfactory cues such as DMS to navigate.

Across many animal taxa, body odor can provide important information about an individual’s sex, age, diet, breeding condition, health, and social status. Birds use preen oils secreted by the uropygial gland for

feather maintenance and water proofing, but these secretions probably also play a role in chemical communication. Several species of birds can distinguish conspecifics from heterospecifics using only smell, e.g., Dark-eyed Juncos and Bohemian Waxwings. Other species of birds may use olfaction during mate selection and recognizing specific individuals.

Several species of birds use olfaction when selecting nest-building materials. For example, male European Starlings prefer plants with odors that are

familiar to them from their natal nest. Incorporating these green, aromatic

plants into their nests reduces pathogen and ectoparasite loads normally found in their nest environments. Finally, some birds are apparently able to recognize the odors of possible predators and use this information to reduce predation risk. Studies of the ability of birds to

detect the odors of predators focused mainly on passerines. For example, European Starlings detected and responded to

the odors of black rat urine samples placed in their nests. Similarly, male House Sparrows recognized the

odor of house mouse urine when selecting nest boxes for nesting or

roosting, and Spotless Starlings, Rock Sparrows, and Western

Jackdaws preferred to nest in control cavities than in those scented with ferret scent (From: Creece et al. 2025).

A well-developed sense of smell in birds? -- Among vertebrates, the sense of smell is mediated by olfactory receptors (ORs) expressed in sensory neurons within the olfactory epithelium. Comparative genomic studies suggest that the olfactory acuity of mammalian species correlates positively with both the total number and the proportion of functional OR genes encoded in their genomes. In contrast to mammals, avian olfaction is poorly understood, with birds widely regarded as relying primarily on visual and auditory inputs. Steiger et al. (2008) found that in nine bird species from seven orders (Blue Tit, Cyanistes caeruleus; Black Coucal, Centropus grillii; Brown Kiwi, Apteryx australis; Canary, Serinus canaria; Galah, Eolophus roseicapillus; Red Jungle Fowl, Gallus gallus; Kakapo, Strigops habroptilus; Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos; and Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea), most amplified OR sequences are predicted to be from potentially functional genes. This finding is somewhat surprising as one previous report suggested that most OR genes in a bird (Red Jungle Fowl) genomic sequence were non-functional pseudogenes. Steiger et al. (2008) also show that it is not the estimated proportion of potentially functional OR genes, but rather the estimated total number of OR genes that correlates positively with relative olfactory bulb size, an anatomical correlate of olfactory capability. We further demonstrate that all the nine bird genomes examined encode OR genes belonging to a large gene clade, the expansion of which appears to be a shared characteristic of class Aves. In summary, these findings suggest that olfaction in birds may be a more important sense than generally believed.

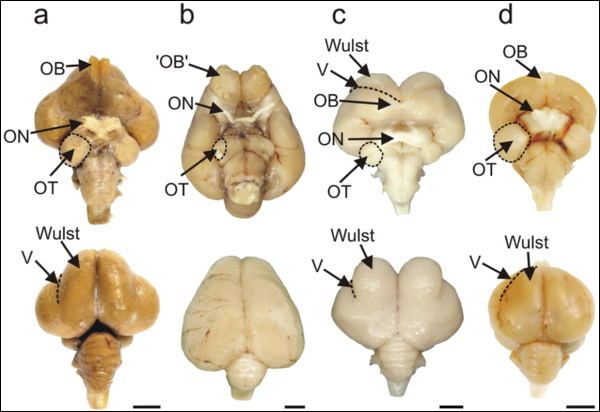

| a. Emu | b. Kiwi | c. Barn Owl | d. Rock Pigeon |

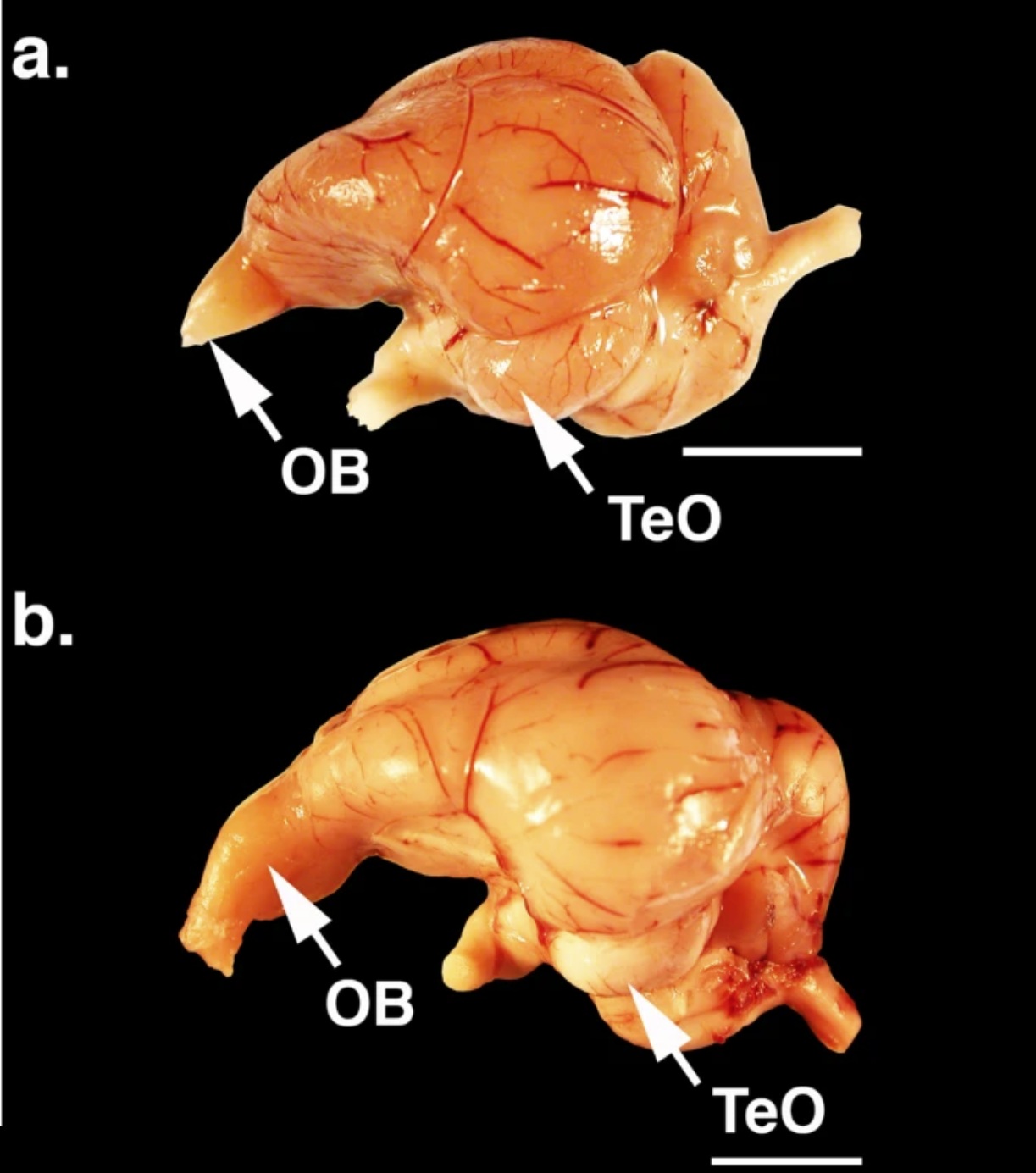

Visual processing areas of the brains of four species of birds. Ventral and dorsal views of the brains of (a) Emu (diurnal, flightless);

(b) Kiwi (nocturnal, flightless); (c) Barn Owl (nocturnal, flying), and (d) Rock Pigeon (diurnal, flying). OT: optic tectum; ON: optic nerve;

OB; olfactory bulb (which actually consists of a cortical-like sheet in the adult kiwi; V: vallecula. Note the reduced diameter of the

optic nerve in Kiwi compared with that in the three other species (see text for actual measurements). In the dorsal view of Kiwi, note the caudal extension

of the large telencephalic hemispheres that completely hide the underlying midbrain. Note also in Kiwi that there is no obvious bulge on the

dorsum of the hemisphere that identifies the Wulst in species such as Barn Owl and Emu.

Scale bars: Emu, 1 cm; Kiwi, Barn Owl and Rock Pigeon: 0.5 cm (From: Martin et al. 2007).

Kiwi (Apterygidae) show minimal reliance on vision as indicated by eye structure and brain structures, and increased reliance upon tactile and olfactory information.This lack of reliance on vision and increased reliance upon tactile and olfactory information in Kiwi is markedly similar to the situation in nocturnal mammals that exploit the forest floor. That Kiwi and mammals evolved to exploit these habitats quite independently provides evidence for convergent evolution in their sensory capacities that are tuned to a common set of perceptual challenges found in forest floor habitats at night and which cannot be met by the vertebrate visual system. Martin et al. (2007) proposed that the Kiwi visual system has undergone adaptive regressive evolution driven by the trade-off between the relatively low rate of gain of visual information that is possible at low light levels, and the metabolic costs of extracting that information.

|

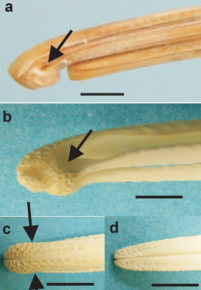

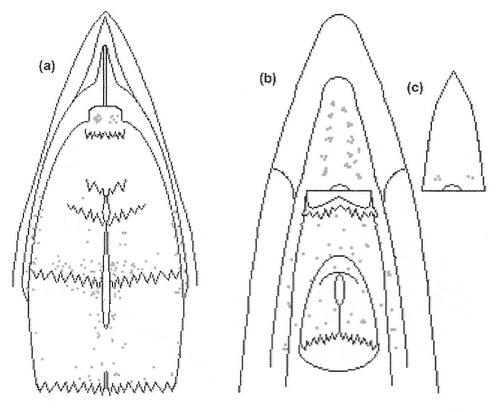

Nostrils and sensory pits at the bill tip of Kiwi. a, Lateral view of the bill tip of a museum skin specimen with the rhamphotheca intact and showing the position of the nostril (arrow). b–e, bones of the bill tip. b latero-ventral view of the maxilla showing the complex blunt shape of the bill tip whose surface is covered with closely packed sensory pits; the approximate position of the nostril is indicated (arrow). c, dorsal view of the maxilla with the approximate positions of the nostrils indicated (arrows), d, dorsal view of the mandible showing that sensory pits are found at the bill tips within the mouth. All scale bars 5 mm. (From: Martin et al. 2007). |

Pattern of pits (that contain mechanoreceptors) in the bill-tips of five species of kiwis. (a) Southern

Brown Kiwi (Apteryx australis), (b) Little Spotted Kiwi (A. owenii), (c) Great Spotted Kiwi

(A. haastii), (d) Okarito Brown Kiwi (A. rowi), and (e) North Island Brown Kiwi (A. mantelli).

Photographs to scale, scale bar = 5 mm (From: Cunningham et al. 2007).

Kiwis are unique among birds in having the opening of their nostrils close to the tip of the maxilla. In all other birds, the nostrils open externally close to the base of the bill, or internally in the roof of the mouth. Martin et al. (2007) provide evidence that Kiwi bill tips are the focus of both olfactory and tactile information. Inspection of prepared skulls shows that clustered around the tips of both the maxilla and mandible, on both internal and external surfaces, is a high concentration of sensory pits. Such pits house clusters of mechanoreceptors (Herbst and Grandry corpuscles) protected by a soft rhamphotheca. These sensory pits function in foraging to detect objects touching or close to the bill tips. In Kiwi, the sensory pits cover the entire surface of the tip of the maxilla and almost encircle the nostrils that open laterally ca. 3 mm behind the bill tip, suggesting that the bill tip is a focus for gaining both tactile and olfactory information for guiding the bill when foraging.

Brains of (a) a Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus) and (b) a Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). The arrows indicate the olfactory bulbs (OB) and optic lobes (TeO). Scale bars = 10 mm.

Evolution of olfaction in non-avian theropod dinosaurs and birds -- Little is known about the olfactory capabilities of extinct basal (non-neornithine) birds or the evolutionary changes in olfaction that occurred from non-avian theropods through modern birds. Although modern birds are known to have diverse olfactory capabilities, olfaction is generally considered to have declined during avian evolution as visual and vestibular sensory enhancements occurred in association with flight. To test the hypothesis that olfaction diminished through avian evolution, Zelenitsky et al. (2011) assessed relative olfactory bulb size, here used as a neuroanatomical proxy for olfactory capabilities, in 157 species of non-avian theropods, fossil birds and living birds. Relative olfactory bulb size increased during non-avian maniraptoriform evolution, remained stable across the non-avian theropod/bird transition, and increased during basal bird and early neornithine evolution. From early neornithines through a major part of neornithine evolution, the relative size of the olfactory bulbs remained stable before decreasing in derived neoavian clades. These results show that, rather than decreasing, the importance of olfaction actually increased during early bird evolution, representing a previously unrecognized sensory enhancement. The relatively larger olfactory bulbs of earliest neornithines, compared with those of basal birds, may have endowed neornithines with improved olfaction for more effective foraging or navigation skills.

Olfactory bulbs - Bambiraptor, Lithornis, Presbyornis,

and present-day pigeon

Taste:

Diagram illustrating the distribution of taste buds (~250 total) in the oral cavity of a domestic chicken. Each dot = one taste bud.

(a) palate, (b) tongue and floor of the oral cavity, and (c) tip of tongue moved to the side to show taste buds on floor of oral cavity

(From: Kudo et al. 2008).

Taste bud from the tongue of an Emu. Arrows demarcate the taste bud and the * indicates the taste bud pore (Source: Crole and Soley 2009). |

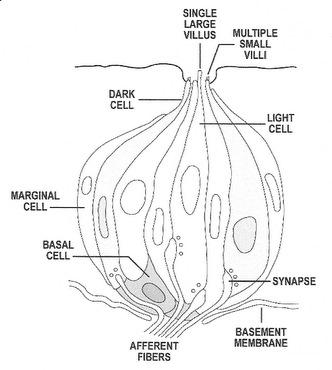

Structure of a typical vertebrate taste bud (Source: Northcutt 2004). |

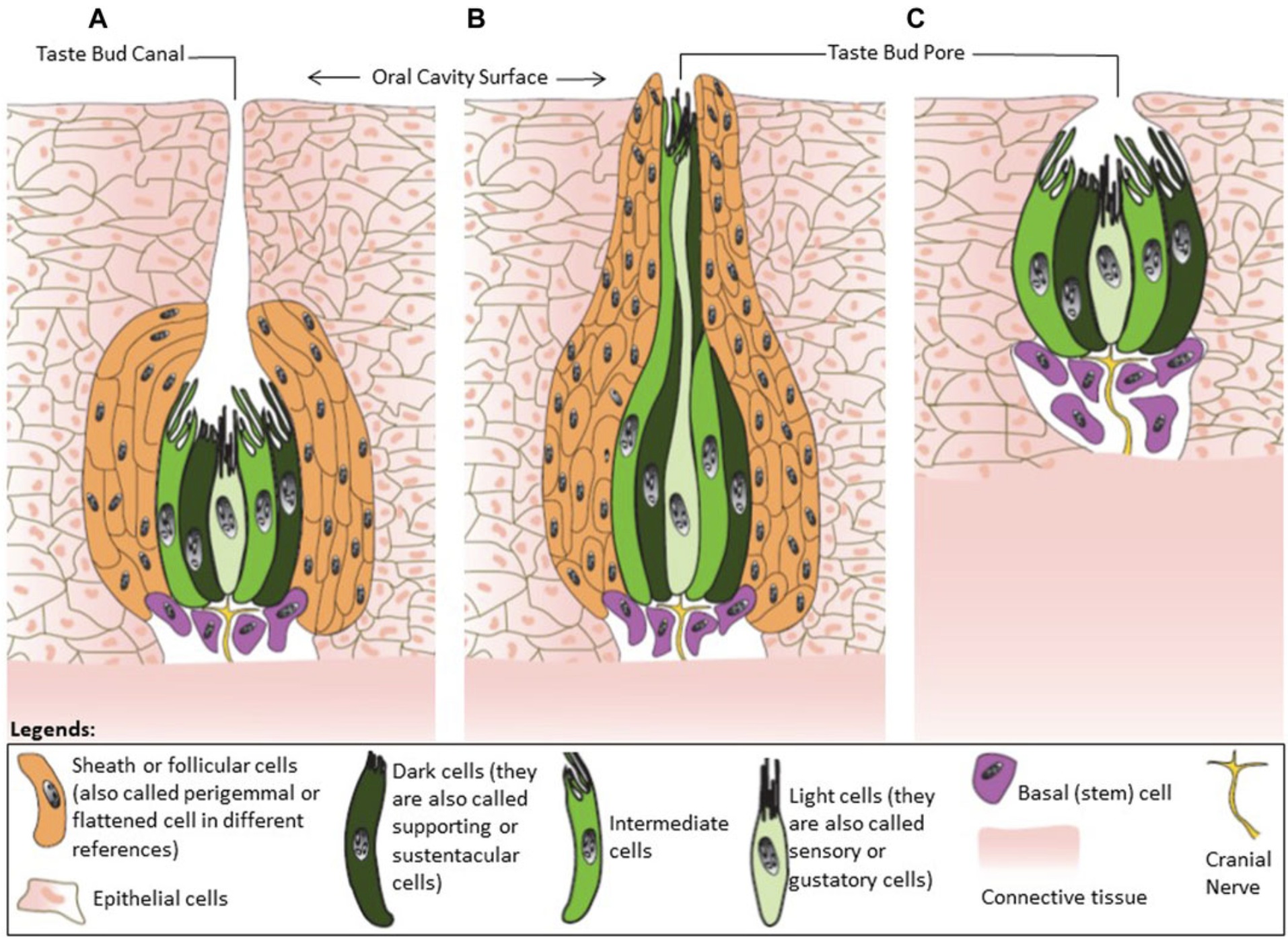

Classification of avian taste buds. (A) Type I is an ovoid taste bud enwrapped by follicular cells. (B) Type II have an elongated shape.

(C) Type III has no follicular cells. In chickens, 55% of the cells in the taste buds are supporting cells (also called dark cells). The function

of these cells is to remove the neurotransmitters from the extracellular environment and terminate signal transmission. These cells are

also responsible for transduction of the salty taste. Sensory cells (also called light cells) mediate sweet, umami, and bitter tastes, with cell

only having receptors for one of those tastes. Intermediate cells, the least numerous cell in the taste buds, receive signals from the sensory

cells and enhance the responses to a variety of tastants. Basal cells are undifferentiated cells located at the bottom of taste buds, and are

the precursors of the other three types of cells in taste buds (From: Niknafs et al. 2023).

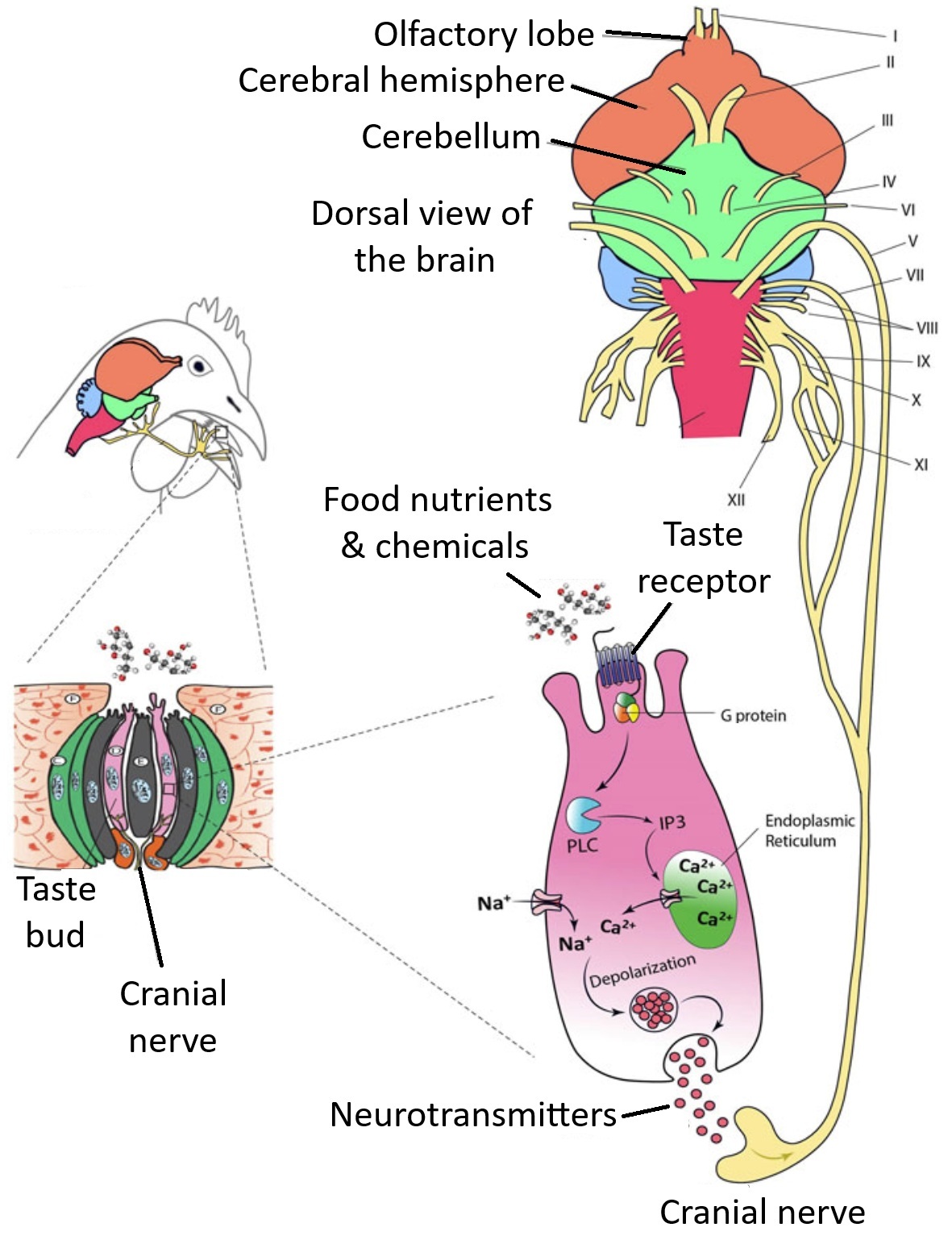

Nutrients and other chemical compounds present in food such as glucose, amino acids, minerals, and

organic acids come into contact with taste sensory cells in the oral cavity. The substances bind to membrane

receptors and trigger a cascade of biochemical reactions in the sensory cell. As a result of these reactions,

sensory cells release neurotransmitters and stimulate cranial nerves that will then, in turn, stimulate the

cells in the gustatory cortex of the brain. Birds have 12 cranial nerves and nerves V, VII, IX, X, and XI

are involved in transmitting taste information (From: Niknafs et al. 2023).

Foraging Dunlin

Long-billed Curlew

Barrier Island foraging strategies

Literature Cited

Bird, C. D., and N. J. Emery. 2009. Rooks used stones to raise the water level to reach a floating worm. Current Biology 19: 1410-1414.

Clayton, N. S. & Dickinson, A. D. 1998. What, where and when: evidence for episodic-like memory during cache recovery by Scrub Jays. Nature 395: 272- 278.

Creece et al. 2025. Past research and future directions in understanding how birds use their sense of smell. Ibis 167: 853–881.

Crole, M. R., and J. T. Soley. 2009. Morphology of the tongue of the Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). II. Histological features. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 76: 347-361.

Cunningham, S. J., M. R. Alley, and I. Castro. 2011. Facial bristle feather histology and morphology in New Zealand birds: implications for function. Journal of Morphology 272: 118-128.

Cunningham et al. 2007. A new prey-detection mechanism for kiwi (Apteryx spp.) suggests convergent evolution between paleognathous and neognathous birds. Journal of Anatomy 211: 493–502.

Curcio, C.A. & K.A. Allen. 1990. Topography of ganglion cells in human retina. J. Comp. Nuerol. 300:5-25.

Emery, N. J. and N. S. Clayton. 2005. Evolution of the avian brain and intelligence. Current Biology 15: R946-R950.

Emmerton, J., & J. D. Delius. 1980. Wavelength discrimination in the 'visible' and ultraviolet spectrum in pigeons. J. Comp. Physiol. A 141: 47-52.

Firestein, S. 2001. How the olfactory system makes sense of scents. Nature 413: 211-218.

Fox, R., S.W. Lehmkuhle, & D.H. Westendorf. 1976. Falcon visual acuity. Science 192:263-265.

Grigg et al. 2017. Anatomical evidence for scent guided foraging in the turkey vulture. Scientific Reports 7: 17408.

Griesser, M., Drobniak, S. M., Graber, S. M., & van Schaik, C. P. (2023). Parental provisioning drives brain size in birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(2), e2121467120.

Gunturkun, O. 2000. Sensory physiology: vision. Pp. 1 - 19 in Sturkie's Avian Physiology, fifth edition. Academic Press, San Diego.

Halata, Z., M. Grim , and K. I. Bauman. 2003. Friedrich Sigmund Merkel and his Merkel cell, morphology, development, and physiology: Review and new results. The Anatomical Record 271A: 225-239.

Heldstab et al. 2022. The economics of brain size evolution in vertebrates. Current Biology 32: R697-R708.

Jarvis, E.D., O. Güntürkün, L. Bruce, A. Csillag, H. Karten, W. Kuenzel, L. Medina, G. Paxinos, D. J. Perkel, T. Shimizu, G. Striedter, M. Wild, G. F. Ball, J. Dugas-Ford, S. Durand, G. Hough, S. Husband, L. Kubikova, D. Lee, C.V. Mello, A. Powers, C. Siang, T.V. Smulders, K. Wada, S.A. White, K. Yamamoto, J. Yu, A. Reiner, and A. B. Butler. 2005. Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6:151-159.

Karten, H.J. 1997. Evolutionary developmental biology meets the brain: The origins of mammalian cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2800-2804.

Knudson, E. 2002. Instructed learning in the auditory

localization pathway of the Barn Owl. Nature 417:322-328.

Ksepka et al. 2020. Tempo and Pattern of Avian Brain Size Evolution. Current Biology 30: 2026-2036.

Krishnan, A. 2023. Biomechanics illuminates form–function relationships in bird bills. Journal of Experimental Biology 226: jeb245171.

Kudo, K., S. Nishimura, and S. Tabata. 2008. Distribution of taste buds in layer-type chickens: scanning electron microscopic observations. Animal Science Journal 79: 680-685.

Lesku,J. A. and R. C. Rattenborg. 2014. Avian sleep. Current Biology 24: R12-R14.

Lesku, J. A. and M. H. Schmidt. 2022. Energetic costs and benefits of sleep. Current Biology 32: R656-R661.

Martin, G. R., K.-J. Wilson, J. M. Wild, S. Parsons, M. F. Kubke, and J. Corfield. 2007. Kiwi forego vision in the guidance of their nocturnal activities. PLoS ONE 2: e198.

Mason, J.R, & L. Clark. 2000. The chemical senses of birds. Pp. 39 - 56 in Sturkie's Avian Physiology, fifth edition. Academic Press, San Diego.

Medina, L. and A. Reiner. 2000. Do birds possess homologues of mammalian primary visual, somatosensory and motor cortices? Trends Neurosci. 23:1-12.

Nebel, S., D. L. Jackson, and R. W. Elner. 2005. Functional association of bill morphology and foraging behaviour in Calidrid sandpipers. Animal Biology 55: 235-243.

Nevitt, G. 1999. Foraging by Seabirds on an Olfactory Landscape. American Scientist 87:46-54.

Niknafs et al. 2023. The avian taste system. Frontiers in Physiology 14: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1235377.

Northcutt, R. G. 2004. Taste buds: development and evolution. Brain, Behavior and Evolution 64: 198-206.

Pohnert, G., M. Steinke and R. Tollrian. 2007. Chemical cues, defence metabolites and the shaping of pelagic interspecific interactions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 22: 198-204.

Piersma, T., R. van Aelst, K. Kurk, H. Berkhoudt, & L.R.M. Maas. 1998. A new pressure sensory mechanism for prey detection in birds: the use of principles of seabed dynamics? Proceedings of the Royal Society B 265:1377-1383.

Prior, H., A. Schwarz, and O. Güntürkün. 2008. Mirror-induced behavior in the magpie (Pica pica): evidence of self-recognition. PLoS Biology 6: e202.

Raby, C. R., D. M. Alexis, A. Dickinson, and N. S. Clayton. 2007. Planning for the future by Western Scrub-Jays. Nature 445: 919-921.

Rattenborg, N.C., S.L. Lima, and C.J. Amlaner. 1999. Half-awake to the risk of predation. Nature 397:397.

Rattenborg, N. C., B. H. Mandt, W. H. Obermeyer, P. J. Winsauer, R. Huber, M. Wikelski, and R. M. Benca1. 2004. Migratory Sleeplessness in the White-Crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii). PLoS Biology 2: e212.

Rohwer et al. 2021. Filoplume morphology covaries with their companion primary suggesting that they are feather-specific sensors. Ornithology 138: 1–11.

Saxon, R. 1996. Ontogeny of the cutaneous sensory organs. Microscopy Research and Technique 34: 313-333.

Shan et al. 2025. Avian neuronal morphology reveals pallial adaptations in Pigeons (Columba livia). Avian Research, in Press, Journal Pre-proof.

Schultz, J. D. and B. A. Schlinger. 1999. Widespread accumulation of [3H]testosterone in the spinal cord of a wild bird with an elaborate courtship display. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 10428–10432.

Sonnenberg, B. R., C.L. Branch, A.M. Pitera, E. Bridge, and V.V. Pravosudov (2019). Natural Selection and Spatial Cognition in Wild Food-Caching Mountain Chickadees. Curr. Biol. 29: P670-P676.

Steiger, S. S., A. E. Fidler, M. Valcu, and B. Kempenaers. 2008. Avian olfactory receptor gene repertoires: evidence for a well-developed sense of smell in birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275: 2309-2317.

Sultan, F. 2005. Why some bird brains are larger than others. Current Biology 15: R649-R650.

Ulinski, P.S. 1983. Dorsal Ventricular Ridge: A Treatise on Forebrain Organization in Reptiles and Birds. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

van Hasselt et al. 2025. Sleep pressure causes birds to trade asymmetric sleep for symmetric sleep. Current Biology 35:1918-1926.

von Eugen et al. 2022. Avian neurons consume three times less glucose than mammalian neurons. Current Biology 32: 4306-4313.

Witmer, L. M. 1995. Homology of facial structures in extant archosaurs (birds and crocodilians), with special reference to paranasal pneumaticity and nasal conchae. Journal of Morpholgy 225: 269-327.

Yokosuka, M., A. Hagiwara, T. R. Saito, N. Tsukahara, M. Aoyama, Y. Wakabayashi, S. Sugita, and M. Ichikawa. 2009. Histological properties of the nasal cavity and olfactory bulb of the Japanese Jungle Crow Corvus macrorhynchos. Chemical Senses 34: 581-593.

Zelenitsky, D. K., F. Therrien, R. C. Ridgely, A. R. McGee, and L. M. Witmer. 2011. Evolution of olfaction in non-avian theropod dinosaurs and birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278: 3625-3634.

Ziolkowski et al. 2022. Tactile sensation in birds: Physiological insights from avian mechanoreceptors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 74: 102548.

Useful links:

The Life of Birds: Bird Brains